New Bolton Center’s Dr. Rose Nolen-Walston conducted two separate studies on blood transfusions in horses: one examined whether blood from horses can be taken once a month and stored successfully for use in transfusions; and another examined the consequences of giving transfusions to horses with blood that was not crossmatched to their blood type. Nolen-Walston, Assistant Professor of Large Animal Internal Medicine, collaborated with two New Bolton Center colleagues on the studies.

It’s a scary day when your horse needs a blood transfusion. Maybe he got injured in the field, or bled a lot after castration. Maybe it’s a mare that bled from her uterine artery after foaling, something seen more commonly as mares age and have more offspring. Maybe it’s a foal that ingested antibodies that attacked its own red blood cells after drinking the first milk from its dam. Sometimes horses with fungal infections in the guttural pouch (an airsac right behind the jaw) bleed profusely, as do horses undergoing sinus surgery. But whatever it is, red blood cells carrying oxygen to the organs are essential for life; when there aren’t enough of them, the very machinery of the body begins to shut down rapidly. Getting that blood into your horse is essential, and often can be a race against the clock.

It’s a scary day when your horse needs a blood transfusion. Maybe he got injured in the field, or bled a lot after castration. Maybe it’s a mare that bled from her uterine artery after foaling, something seen more commonly as mares age and have more offspring. Maybe it’s a foal that ingested antibodies that attacked its own red blood cells after drinking the first milk from its dam. Sometimes horses with fungal infections in the guttural pouch (an airsac right behind the jaw) bleed profusely, as do horses undergoing sinus surgery. But whatever it is, red blood cells carrying oxygen to the organs are essential for life; when there aren’t enough of them, the very machinery of the body begins to shut down rapidly. Getting that blood into your horse is essential, and often can be a race against the clock.

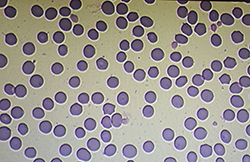

Blood transfusions in horses share a lot of similarities with humans, but there are some vital differences. The first has to do with matching blood types, a laboratory test to ensure that the recipient won’t react negatively to the transfused blood. Unlike humans, who have just three main blood types (A, B, and O), horses have seven blood groups: A, C, D, K, P, Q, and U. Furthermore, each group can have multiple cell membrane proteins referred to as factors a, b, c, d, e, f, or g. The blood type refers to both group and factor, so each horse has a blood type such as Qa or Pd. Doing the math, this leads to over 400,000 combinations! So the first major difference between humans and horses is that we veterinarians very rarely can give truly “matched” blood.

However, there’s an upside: in humans, giving unmatched blood often results in a serious transfusion reaction, where the recipient’s body attacks the red blood cells, causing fever, anemia, and sometimes even anaphylactic shock. This is because humans have naturally occurring “alloantibodies,” or antibodies that you are born with that recognize and attack foreign blood types. With the horse, naturally occurring alloantibodies occur in fewer than 10% of the population, so the first transfusion a horse receives often does not need to be a match. For second and subsequent transfusions, though, the horse will develop antibodies against the blood type they received, so blood matching is essential for further transfusions.

The second main difference in equine transfusion medicine is that there are no blood banks for horses, and horse blood can only be stored for a month. Horses need transfusions rarely enough that most veterinary hospitals manage the challenge by maintaining a herd of horses that can donate blood when needed. Furthermore, due to their size, horses requiring a transfusion often need 20 or more pints of blood. That’s a lot to try to store over long periods of time, especially taking into account multiple blood types. If a veterinarian chooses to do a blood match for a patient, s/he would need to go into the field and obtain blood samples from all donors and perform a crossmatch. This takes up valuable time, delays the transfusion, and is expensive and labor intensive.

The second main difference in equine transfusion medicine is that there are no blood banks for horses, and horse blood can only be stored for a month. Horses need transfusions rarely enough that most veterinary hospitals manage the challenge by maintaining a herd of horses that can donate blood when needed. Furthermore, due to their size, horses requiring a transfusion often need 20 or more pints of blood. That’s a lot to try to store over long periods of time, especially taking into account multiple blood types. If a veterinarian chooses to do a blood match for a patient, s/he would need to go into the field and obtain blood samples from all donors and perform a crossmatch. This takes up valuable time, delays the transfusion, and is expensive and labor intensive.

These challenges brought to light a couple of questions we decided to address in a pair of studies on equine blood transfusions.

- Can blood samples from the donor herd be taken once a month and stored in the refrigerator, so when a patient is admitted that needs a transfusion, the crossmatch can be performed without having to go out (often at night or during inclement weather) and take samples from the donor herd?

- As naturally occurring alloantibodies in horses are rare, what are the ramifications of giving an unmatched transfusion? Do the horses have medical consequences? Do the red blood cells lastas long in the blood stream?

Can blood samples from the donor herd be taken once a month and stored successfully?

Dr. Michelle Harris and I performed a study examining whether blood samples that were stored for a month gave accurate results when used for crossmatching tests. Blood samples banked for up to one month are typically used to perform pre-transfusion testing in small animals and humans, but this method had not been validated using blood from horses. We hypothesized that the compatibility of equine blood samples is reproducible using donor blood samples stored for up to four weeks. To test this hypothesis, we took blood samples from six healthy adult horses and tested them against fresh blood samples weekly for one month. The crossmatch results were scored and then compared to identify changes of compatibility in each of the four tests. In addition, repeatability of the crossmatch technique itself was assessed by performing six iterations of the procedure in immediate succession, with fresh blood from three horses.

The results were unexpected. Unlike dogs, cats, and humans, horse blood became more “reactive” as it sat in storage, leading to false positive results (horses appearing to be poor matches when, in fact, their blood matched well). This data suggests that fresh samples should be collected from potential equine donors before crossmatching equine blood. The research was published in the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, allowing other veterinarians across the world to access this information.

The results were unexpected. Unlike dogs, cats, and humans, horse blood became more “reactive” as it sat in storage, leading to false positive results (horses appearing to be poor matches when, in fact, their blood matched well). This data suggests that fresh samples should be collected from potential equine donors before crossmatching equine blood. The research was published in the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, allowing other veterinarians across the world to access this information.

What are the ramifications of giving a transfusion of unmatched blood to a horse?

Dr. Joy Tomlinson and I examined the life span of red blood cells in transfused blood, comparing transfusions to horses in which the blood types crossmatched well, and those that had incompatible crossmatch tests. For this study, funded by the Region 15 Arabian Horse Association and the Firestone Foundation, we collaborated with a local Thoroughbred rescue organization, using young racehorses that were being rested for lameness problems before being adopted out to new homes. We identified 10 pairs of horses: nine pairs that had incompatible blood types, and one pair with blood that crossmatched well and served as a control. Each horse underwent a transfusion using four liters (a gallon) of fresh whole blood that had been labelled with biotin, a red blood cell marker. The biotin allowed us to identify which cells in the horses’ bloodstreams were their original red blood cells, and which came from the transfused blood. Post-transfusion blood samples were collected at 1 hour and then at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 days. The samples were then analyzed by flow cytometry, a high-tech technique that uses lasers to count and sort microscopic cells suspended in fluid.

The study showed that using well-matched blood, the average half-life of a transfused red blood cell was 33.5 days, whereas incompatible blood cells had half-lives of only 4.7 days. Additionally, horses undergoing transfusions with crossmatched incompatible blood were more likely to have fevers during and after blood transfusion. None of the horses had reactions that were severe or life-threatening. We concluded that crossmatch incompatibility was predictive of febrile transfusion reaction and shortened transfused red blood cell survival. Therefore, we recommended that crossmatch testing be performed prior to transfusions in horses, whenever feasible. However, if a well-matched donor is not available or cannot be identified, transfusion of incompatible whole blood can be considered in life-threatening conditions.

The study showed that using well-matched blood, the average half-life of a transfused red blood cell was 33.5 days, whereas incompatible blood cells had half-lives of only 4.7 days. Additionally, horses undergoing transfusions with crossmatched incompatible blood were more likely to have fevers during and after blood transfusion. None of the horses had reactions that were severe or life-threatening. We concluded that crossmatch incompatibility was predictive of febrile transfusion reaction and shortened transfused red blood cell survival. Therefore, we recommended that crossmatch testing be performed prior to transfusions in horses, whenever feasible. However, if a well-matched donor is not available or cannot be identified, transfusion of incompatible whole blood can be considered in life-threatening conditions.

If you are interested in sponsoring a research project at New Bolton Center, please contact Carol Pooser at cpooser@vet.upenn.edu or 215-898-1482.