Sprout, now a five-month-old French Bulldog, has seen some tough times in his young life. At five weeks old, Sprout couldn’t keep any food down. His owner, French Bulldog breeder Virginia Cowger, knew something was very wrong. When she brought the dog to her vet, Dr. Liz Bruce, VMD, in Easton, Maryland, Dr. Bruce suspected a persistent right aortic arch.

Sprout, now a five-month-old French Bulldog, has seen some tough times in his young life. At five weeks old, Sprout couldn’t keep any food down. His owner, French Bulldog breeder Virginia Cowger, knew something was very wrong. When she brought the dog to her vet, Dr. Liz Bruce, VMD, in Easton, Maryland, Dr. Bruce suspected a persistent right aortic arch.

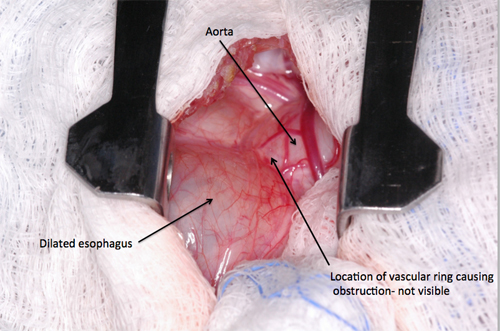

Translation? A persistent right aortic arch is an abnormal development of the major blood vessels in the chest that results in constriction of the esophagus, and in some cases, the trachea. In other words, instead of developing behind the esophagus or trachea, as they should, the major blood vessels, sit on top of these vital passages, thereby restricting the passage of food or air. This, in turn, results in dilatation of the esophagus, regurgitation, and, in some cases, aspiration pneumonia. Puppies often start to show symptoms of distress at the time of weaning, when they are transitioned from liquid to solid foods. In Sprout’s case, his esophageal constriction was so severe that he could not even hold down liquids. At such a young age, this type of developmental malformation can be deadly.

Herself a Penn Vet graduate, Dr. Bruce knew that the team of highly skilled, board-certified surgical specialists at Ryan Hospital would have the experience and resources necessary to address the issue. In fact, Penn Vet surgeons have addressed this malformation many times. But in young dogs suffering from vascular ring anomaly, size really does matter. And Sprout was certainly one of Penn Vet’s tiniest canine surgical patients.

When Mrs. Cowger brought Sprout in for his first consult with soft-tissue surgeon and surgery section chief Dr. David Holt and surgery resident Dr. Chloe Wormser, the tiny puppy weighed just under a pound-and-a-half. On examination, the surgeons quickly assessed that their pint-sized patient was indeed dehydrated, and thoracic radiographs revealed esophageal dilation as well as tracheal deviation: all symptoms consistent with a persistent right aortic arch. In addition, Sprout showed signs of aspiration pneumonia.

With a larger dog, the necessary surgery could have been done laparoscopic, but because of Sprout’s size, the surgical team recommended a left fourth intercostal thoracotomy.

This type of surgical procedure is extensive, and involves entering the space between the ribs, which means opening the chest cavity. Thoracotomies are thought to be one of the most difficult surgical incisions to deal with post-operatively, because they are extremely painful and the pain can prevent the patient from breathing effectively, leading to atelectasis or pneumonia.

This type of surgical procedure is extensive, and involves entering the space between the ribs, which means opening the chest cavity. Thoracotomies are thought to be one of the most difficult surgical incisions to deal with post-operatively, because they are extremely painful and the pain can prevent the patient from breathing effectively, leading to atelectasis or pneumonia.

Historically, this approach has been very difficult on puppies because of their size and their ability to tolerate pain. However, due to advances in nerve block anesthesia and pain management medications, the Penn Vet team felt confident that they would be able to effectively manage Sprout’s surgery and subsequent pain level. With Mrs. Cowger’s approval, Sprout went into surgery.

Once the existence of the persistent right aortic arch was confirmed, the constricting tissue band (ligamentum arteriosum) was cut to free the esophagus and allow for normal flow. Because the esophageal changes can take time to reverse, a gastrostomy tube was placed as part of Sprout’s surgery. This tube allowed for bypass of the esophagus and direct feeding into the stomach, ensuring the puppy would receive all the nutrients he needed during his recovery.

Once the existence of the persistent right aortic arch was confirmed, the constricting tissue band (ligamentum arteriosum) was cut to free the esophagus and allow for normal flow. Because the esophageal changes can take time to reverse, a gastrostomy tube was placed as part of Sprout’s surgery. This tube allowed for bypass of the esophagus and direct feeding into the stomach, ensuring the puppy would receive all the nutrients he needed during his recovery.

But Sprout’s challenges were not over. Since he developed severe aspiration pneumonia after the surgery, he stayed in the Ryan Hospital’s Intensive Care Unit for around the clock care. Within a short time, Sprout was breathing normally again and was gaining weight. Once his team determined he was stable, he was sent home with Mrs. Cowger to recover. And Sprout was sporting a tiny shirt to keep his gastrostomy tube in place.

From left: Dr. Bruce, Mrs. Cowger, Sprout, Dr. Wormser, Dr. Holt

Mrs. Cowger brought Sprout back for consults every couple of weeks after surgery. The surgeons were cautiously optimistic, as he had been gaining weight. Mrs. Cowger started to feed him orally in addition to his gastrostomy tube feedings, which he was tolerating this well. Four weeks after surgery, his gastrostomy tube was removed. However, shortly after his tube was removed, Sprout began to show signs of esophagitis (esophageal inflammation) including dehydration, weight loss, and regurgitation. Once his gastrostomy tube was replaced. he bounced back quickly and has since shown signs of significant improvement. Not only has Sprout has been eating on his own without any further signs of regurgitation, he has also steadily been gaining weight.

The hope is that once Sprout is a little bigger, his  gastrostomy tube can be removed permanently. Mrs. Cowger is grateful for the expert care. “I do everything the right way for my dogs, and that’s why we ended up here at Penn Vet,” she said. “Sprout is growing and thriving again, and I’m really grateful for the care he received from our vet, Dr. Bruce, and the Penn Vet surgical team.”

gastrostomy tube can be removed permanently. Mrs. Cowger is grateful for the expert care. “I do everything the right way for my dogs, and that’s why we ended up here at Penn Vet,” she said. “Sprout is growing and thriving again, and I’m really grateful for the care he received from our vet, Dr. Bruce, and the Penn Vet surgical team.”