Benjamin Spalding was working late when he heard the screams.

He ran outside to investigate and saw that a fox had startled Pete, his 34-year-old Mealy Amazon parrot. As Pete climbed up the side of the backyard aviary, the fox grabbed his foot and tore it off.

Spalding and his wife, Stacey Gehringer, immediately put Pete into his carry cage, got in the car, and headed to an emergency veterinary clinic nearby. Gehringer called the clinic to let them know they were on the way, but the clinic said they couldn’t take Pete as a patient.

“They gave us the name of an animal emergency hospital in New Jersey,” said Spalding. “We called them and got basically the same response.’”

There are few veterinary hospitals close to the Lehigh Valley with experienced Exotics vets on staff. Fortunately, Penn Vet’s Ryan Hospital is one of them. When Gehringer called Ryan’s Emergency Service, she was told to bring Pete in.

Pete was quiet in the car as they made the trip from Allentown, PA to Philadelphia.

Compassionate Care

Dr. La’Toya Latney, Service Head and Attending Clinician of the Exotic Companion Animal Medicine service, was on call when she received the 2:00AM phone call. When she arrived at the hospital, Pete seemed alert, despite having lost a lot of blood. Latney’s primary goal was to stop the bleeding and provide fluid therapy.

Dr. La’Toya Latney, Service Head and Attending Clinician of the Exotic Companion Animal Medicine service, was on call when she received the 2:00AM phone call. When she arrived at the hospital, Pete seemed alert, despite having lost a lot of blood. Latney’s primary goal was to stop the bleeding and provide fluid therapy.

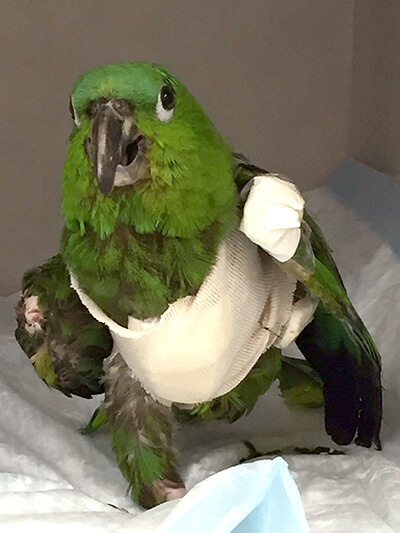

The Emergency team administered sedation and pain medication and tended to Pete’s wounds. His left leg was severed midway below the knee. He also had a small wound on his chest. They placed a supportive bandage on Pete’s leg and kept him comfortable overnight.

Thankfully, despite the blood loss, Pete’s odds of survival were promising, as birds have a unique ability to reproduce red blood cells much faster than humans. It’s been shown that birds can lose 30% of their total blood volume without showing signs of shock. Birds would have to sustain about a 60% loss of blood before there would be a notable change in blood pressure or signs of decompensation.

Thankfully, despite the blood loss, Pete’s odds of survival were promising, as birds have a unique ability to reproduce red blood cells much faster than humans. It’s been shown that birds can lose 30% of their total blood volume without showing signs of shock. Birds would have to sustain about a 60% loss of blood before there would be a notable change in blood pressure or signs of decompensation.

“This goes back to their beautiful design,” explained Latney. “Since they’re designed to fly, birds need a lot of oxygen. So the amount of red blood cells in their system is almost double the amount humans have. I wasn’t extremely concerned because, provided he was healthy, Pete would regenerate a large blood loss within a 24 to 48-hour period.”

Pete was transferred from the Emergency Service to the Exotics ward the following morning. There, he had his blood tested, was given antibiotics, and was scheduled for a computerized tomography (CT) scan.

Dr. Wilfried Mai, Associate Professor of Radiology, performed the CT scan, which would enable Latney to characterize what was going on underneath the skin, since physical exams alone do not always reveal how much damage has been done internally.

“With this imaging, we were able to see the full nature of Pete’s injury, which really helped with surgical planning,” said Latney. “We got Pete into surgery within 48 hours.”

“With this imaging, we were able to see the full nature of Pete’s injury, which really helped with surgical planning,” said Latney. “We got Pete into surgery within 48 hours.”

Pete’s anesthesia was administered by veterinary technician Carly Carpenter and overseen by Dr. Giacomo Gianotti, Assistant Professor of Clinical Anesthesia. Surgery was performed by Latney and Dr. Michael Mison, Clinical Associate Professor of Surgery. They removed some of the damaged tissue that had been infected from the bite. The femur and hip bones were all intact. Thankfully, they were able to salvage a bit of the leg below the knee and close the wound over it.

Pete seemed much more comfortable following the surgery.

“Pete seemed to appreciate that we were trying to help him,” said Latney. “He was affectionate and easy to care for, and handled hospitalization very well.”

“Dr. Latney’s demeanor with her patients is amazing,” said Spalding. “I’ve been to several different vets and they all treated Pete with fear. He’s never seen anything short of a kiss at Ryan Exotics!”

Printed Prototype

Having addressed the relatively short-term goal of closing the wound on Pete’s stump, there were some long-term complications to take into consideration.

Typically, birds that weigh less than 100 grams tend to do well with one leg. Once that weight threshold is exceeded, though, birds often experience pain and arthritis in the remaining leg due to the additional weight burden.

“Given that Pete is a larger-bodied bird, he could experience long-term pain if we don’t provide some type of comparative support,” said Latney.

Never one to back away from a challenge, Latney reached out to Dr. Jonathan Wood, Staff Veterinarian in Neurology and Neurosurgery, with the task of designing a prosthetic leg for Pete.

In last few years, Wood has successfully used 3D-printed models for teaching and planning surgeries, one in particular for a dog named Clubber.

“I wanted to see what we could do for Pete with 3D printing,” said Wood. “We think about animals that will rehab well and animals that will rehab poorly, similar to people. If there was a parrot that wanted to use what we made for him, Pete seemed to be a good candidate.”

Spalding and Gehringer were on board with the idea. “I think it’s really cool,” said Spalding. “I’m a computer guy, a mechanical engineer, so this is right up my alley.”

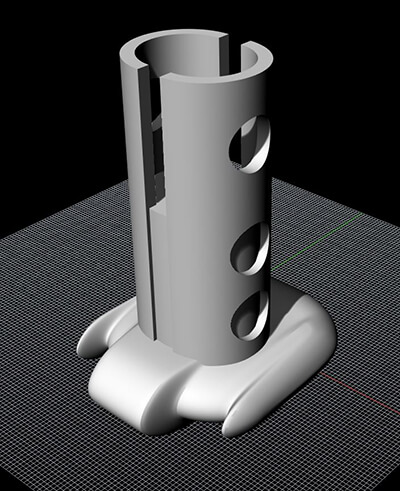

Wood met with Stephen Smeltzer, Digital Fabrication Manager at PennDesign’s Fabrication Lab, to examine the CT scan and formulate a plan. Smeltzer asked questions about birds and bird bones, the weight and stiffness of the prosthetic, and how they might attach it. He then drew sketches.

Wood met with Stephen Smeltzer, Digital Fabrication Manager at PennDesign’s Fabrication Lab, to examine the CT scan and formulate a plan. Smeltzer asked questions about birds and bird bones, the weight and stiffness of the prosthetic, and how they might attach it. He then drew sketches.

“One of the things we love about working with Penn Vet is seeing our technology have an immediate impact in the world,” said Smeltzer. “When we’re working with our students, it’s for a building, product, or landscape that hasn’t been built yet.”

After a few months to allow Pete’s stump to heal and shrink, the team was ready to try the first 3D-printed prototypes.

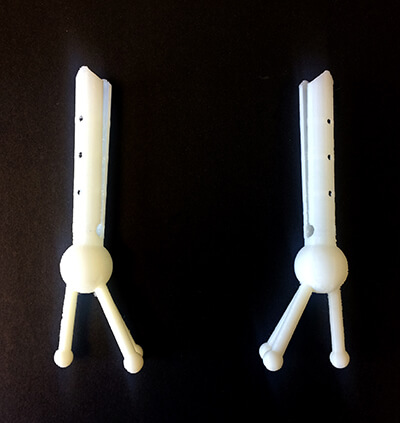

Incredibly thin and fragile, the initial models looked like an actual foot. While they were cosmetically pleasing, the prosthetics were unable to support Pete’s weight.

They would have to go back to the drawing board.

Constructive Collaboration

This time around, Wood enlisted the help of fourth-year student Gregory Kaiman, who had shown a keen interest in the use of 3D printing in veterinary medicine.

Eager to assist, Kaiman explored the option of creating and designing models from scratch, rather than printing from CT scans. After finding a widely used free program online, he became adept at using the software.

“Dr. Wood was kind enough to share some pictures of Pete's stump with measurements, and I began experimenting,” said Kaiman. “After much trial and error, I got a little faster and a little better.”

Learning went both ways. “I had been using one program that was incredibly time-consuming,” said Wood. “Greg was ahead of me, using a different program, and he pushed me to look at other options.”

Together, Wood and Kaiman made some radical changes to the prosthetic design for Pete, moving away from something that looked like an actual foot to something more functional and stable.

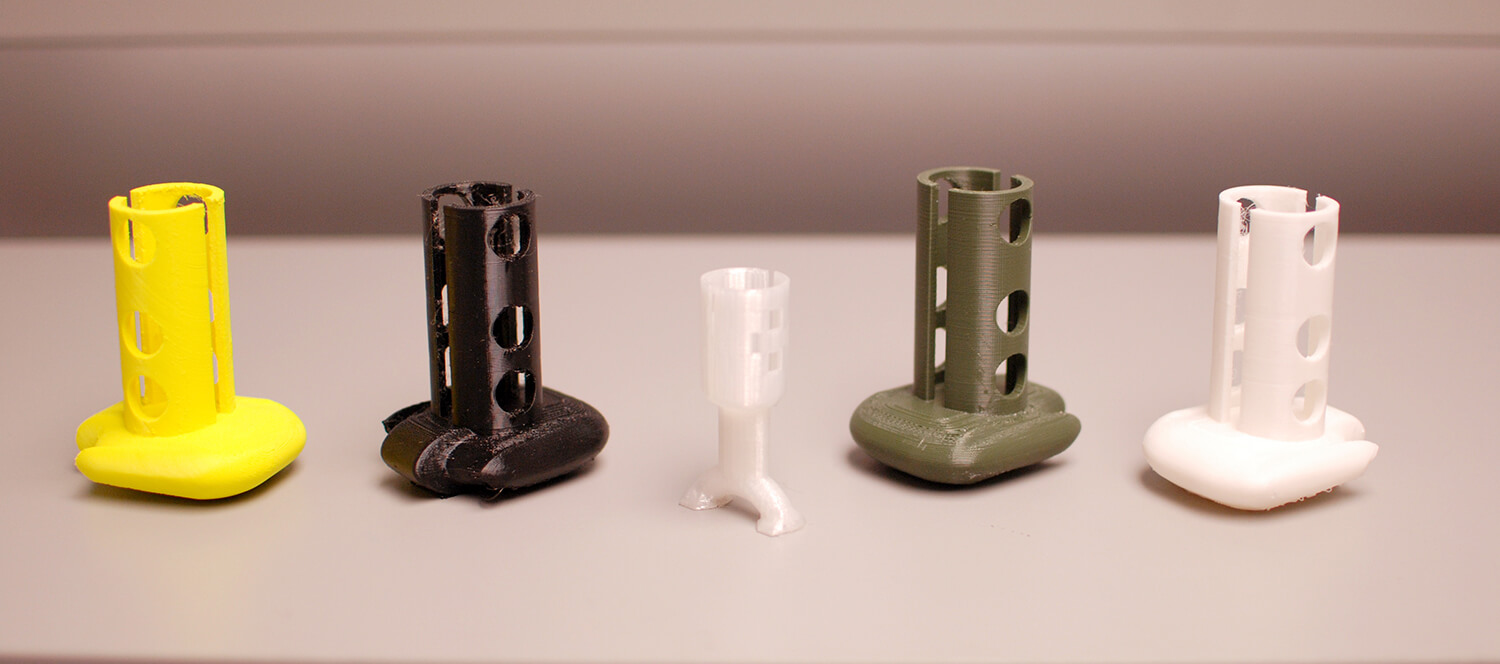

In addition, Kaiman discovered that they could print in different textures, weights, and materials. This breakthrough was a game-changer for the team.

In addition, Kaiman discovered that they could print in different textures, weights, and materials. This breakthrough was a game-changer for the team.

The new prototypes were bulkier, yet more stable, resembling a walking boot. They were made from extruded polymer resin and varied in pliability and hardness.

Though the team was proud of their advances, they were uncertain if Pete would tolerate the new models. Much to their surprise, he willingly allowed Latney to attach the prosthetic.

“He didn’t bite at it, he didn’t try to tear away at it,” said Latney. “At points when he felt stable, he would actually bear weight on it.”

“It was fantastic to see Pete using something that we had made,” said Wood. “This experience changed our thinking about how to approach other amputees.”

“It was fantastic to see Pete using something that we had made,” said Wood. “This experience changed our thinking about how to approach other amputees.”

Unfortunately, while Pete tolerated the prosthetic, it slipped off every time he lifted his leg. The final designs would have to incorporate a system to securely affix the prosthetic to his body.

Future Footwear

A third design is currently being printed at the Fabrication Lab and should be ready for Pete to try out soon. This model is not a walking boot, but rather one for resting. The column is higher and the inside is filled more, to give Pete a surface on which to rest his stump. This will help relieve the pressure and weight from his other leg.

A third design is currently being printed at the Fabrication Lab and should be ready for Pete to try out soon. This model is not a walking boot, but rather one for resting. The column is higher and the inside is filled more, to give Pete a surface on which to rest his stump. This will help relieve the pressure and weight from his other leg.

Wood and Latney are currently working on an attachment system that is safe and comfortable for Pete. They estimate two to three months before the final fitted model is ready.

One option they are exploring is a flight vest to keep the prosthetic secure on Pete’s leg. Since Pete tolerated the padding for his chest wound, the team is confident that he will adjust to an attachment system that goes under and around his wings.

Another idea is to create a boot that is half solid and half soft. The top half would have a sock-like rim that would compress around Pete’s leg, securing it in place.

Another idea is to create a boot that is half solid and half soft. The top half would have a sock-like rim that would compress around Pete’s leg, securing it in place.

“In the meantime, we’ve encouraged Pete’s owners to do physical therapy on the remaining limb,” said Latney.

Even one-legged, Pete is enjoying a full range of activity at home, including climbing. Everyone involved is eager to finalize the prosthetic attachment system to give Pete an even better quality of life at home.

“We are so lucky to have come to Penn Vet,” said Spalding. “If we had ended up anywhere else, Pete wouldn’t have made it. We won’t go anywhere else for his care.”

Follow Penn Vet on Facebook for future updates on Pete’s progress as his new prosthetics become available.

Read how Pete’s case has impacted the training and education of two Penn Vet students.