Fighting on the Front Lines of Infectious Disease

Colonel Eric Lombardini, C’93, G’01, V’01, has lived or worked in 70 countries, on all continents except Antarctica, as a veterinary corps officer rising through the ranks of the U.S. Army.

Board certified in veterinary pathology and veterinary preventive medicine, Lombardini now is stationed in Bangkok, Thailand, where he serves as director of the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences (AFRIMS), the Department of Defense’s largest medical research institute outside of the U.S.

From Diplomacy to Population Health

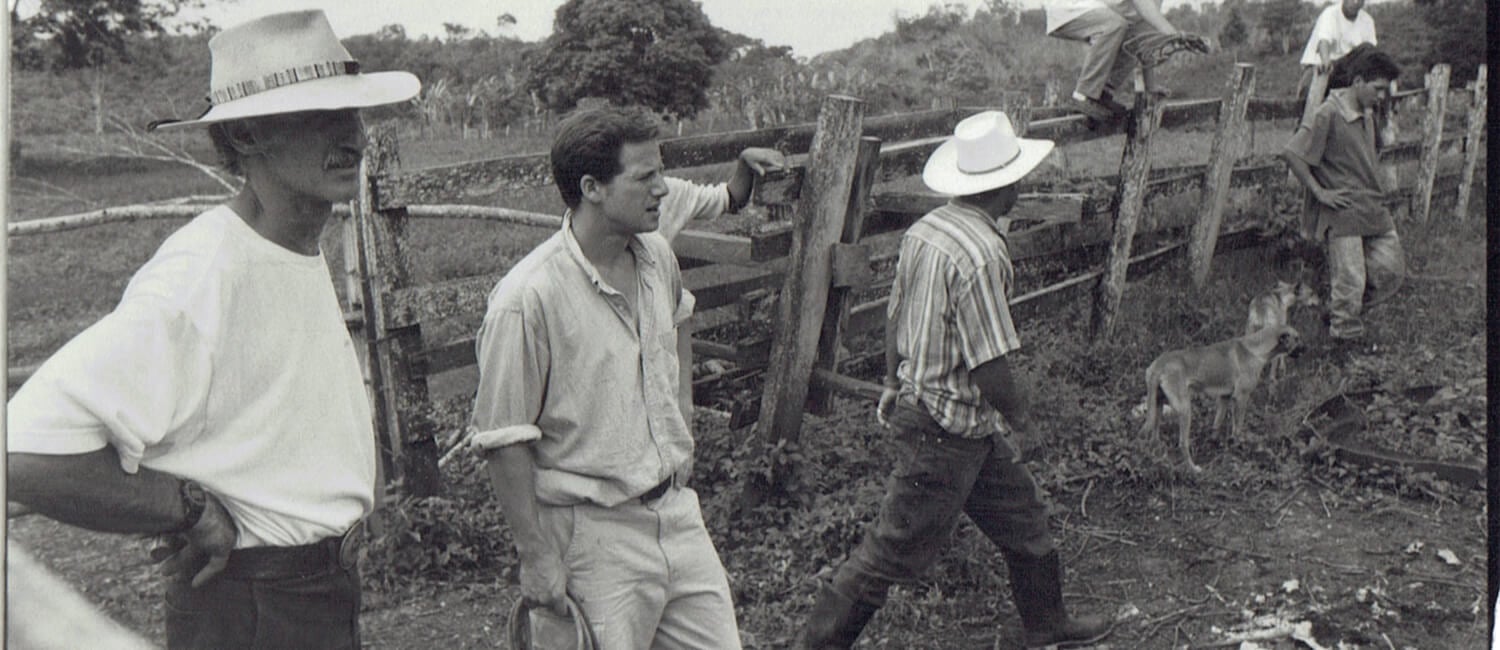

It wasn’t the path Lombardini set on as an undergraduate at Penn studying diplomatic history, with a focus on Africa and the Middle East.

“I simply wasn’t attracted to economics, which was the future of diplomacy, so I turned instead to international development,” said Lombardini, who grew up in Niger and Bahrain as the son of a United States Agency for International Development (USAID) worker. “I decided to see if I could get into vet school as a way into development, specifically population health, looking at large animal production and how to improve nutrition for people in developing nations.”

The only catch was he had never taken any “serious science” courses in college. He eventually caught up on the necessary coursework and was accepted at Penn Vet. During vet school, he also earned a master’s degree in Clinical Epidemiology from Penn, focusing on transmission of the morbilliviruses from domestic stock to wildlife.

Then, in 2001, things took a turn again. Lombardini joined the Army.

“What the military offers is access to places far more challenging, far more difficult to get to than a lot of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), civilian agencies, or academia can offer,” said Lombardini. “The Army has enabled me to have deeper access and impact in times of crisis.”

Crisis, like the unabating pandemic of the last nearly two years

At the Front Lines of Infectious Diseases

AFRIMS was formed in 1958 through an international treaty between Thailand and the U.S. Today, the bi-national institute conducts regional infectious disease surveillance and medical countermeasure research in five countries: Thailand, Cambodia, the Philippines, Nepal, and Australia. It has robust partnerships in combating tropical and emerging infectious diseases with both military and civilian organizations in Vietnam, Mongolia, Bangladesh, India, Lao-PDR, Indonesia, and Bhutan. Headquartered in Bangkok — in the epicenter of more than 50 percent of the world’s population — AFRIMS comprises nine fixed satellite laboratories and hundreds of personnel spanning South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Oceania — all under Lombardini’s direction.

“AFRIMS is an extraordinary place,” he explained. “Sixty years ago, Thailand invited the U.S. Army into the country to help control a cholera outbreak, one of a series that was plaguing the region. The relationship solidified into the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization Laboratory – the SEATO lab — which soon after became AFRIMS.”

Since its founding, AFRIMS has evolved its activities to include infectious disease research and epidemiology, its mission to protect the health and safety of American soldiers and civilians and Southeast Asian nationals across its service area.

The institute also has a storied legacy of success in medical countermeasures development — products, medications, and devices — to diagnose, prevent, or treat diseases that are endemic or emerging in the region. It develops and tests vaccines (Pre-clinical and Phase 1 through Phase 3 clinical trials), rapid diagnostic tests, and treatments for endemic threats and emerging infectious diseases.

“We have played a significant role in disease prevention and countermeasures, such as developing every anti-malarial drug that is FDA approved and two Japanese encephalitis vaccines, dengue and the hepatitis E vaccines, and the world’s only partially effective HIV vaccine,” said Lombardini.

Fighting COVID-19 from Day One

The first COVID-19 case outside of China occurred in Thailand, mobilizing AFRIMS in the pandemic’s earliest days in its role as a regional Research Center of Excellence and World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Center.

“We’ve been very active in COVID-19 surveillance, which is a huge issue — just recently, we were the first to identify the Delta variant in Thailand,” Lombardini said. “And we feed information back to our allies and regional collaborators, as well as into the U.S. Indo-Pacific command. Our information becomes actionable for the various health ministries, U.S. and allied militaries, and interagency partners, such as the CDC and USAID, all of which depend on us for this surveillance data. And as a result, we’re able to protect people and track the spread of disease and how it works.”

Under Lombardini’s leadership, AFRIMS’s COVID-19 attack strategy is multifold.

A key member of the U.S. ambassador to Thailand’s health working group and COVID-19 task force, Lombardini advises on U.S. strategic medical policy in Thailand and throughout Southeast Asia. Additionally, he is responsible for maintaining the scientific and ethical integrity of human, animal, and basic science research happening under AFRIMS’s auspices. And for AFRIMS supporting its partner nations, sharing news, protocols, best practices, and tools to build each country’s capacity to fight COVID-19.

For example, during the earliest days of the outbreak, when testing kits were extremely limited, AFRIMS was one of the first laboratories in Southeast Asia to help screen suspected COVID-19 cases. It distributed hundreds of screening kits to partner laboratories.

AFRIMS has also provided subject matter expertise during the pandemic and is involved with pre-clinical development of therapeutics and COVID-19 vaccines in partnership with regional scientists. This includes helping with the pre-clinical development of ChulaCov19, a collaborative mRNA vaccine being developed in Thailand by Chulalongkorn University and the University of Pennsylvania.

“Over the course of my military career, I’ve seen Penn impact at many different levels.” Lombardini explained. “Penn Vet’s Working Dog Center, for example, has a strong relationship with the Department of Defense. The University developed the platform that the U.S. Army uses to develop resilience in its soldiers, and most recently and specific to AFRIMS, Penn Medicine’s Drew Weissman is working with Chulalongkorn University to help its researchers generate an mRNA vaccine for preventing COVID-19 in developing countries. AFRIMS participated in the vaccine research process. It’s a nice link for me to my alma mater.”

From Battlefield to Lab Bench

Lombardini’s current position is the pinnacle of an Army tenure that began in Fort Polk, Louisiana.

Bethesda, Maryland, 2010.

“I’d asked human resources for an operational unit and was thinking special forces — every special force group has a veterinarian attached to them,” he said. “They said, ‘Absolutely, we’ve got just the place for you — Fort Polk.’ Not quite what I had in mind.”

But it proved a formative assignment, and it’s where Lombardini learned to be a soldier and to lead. As an officer in charge at Fort Polk, he successfully trained a team of veterinary technicians and food inspectors in preparation for deployment.

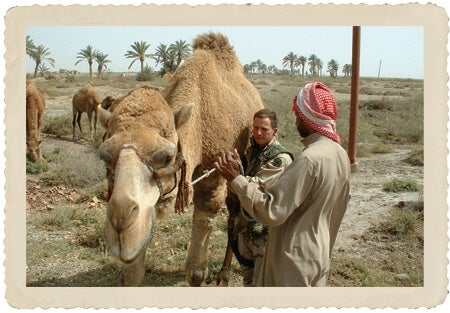

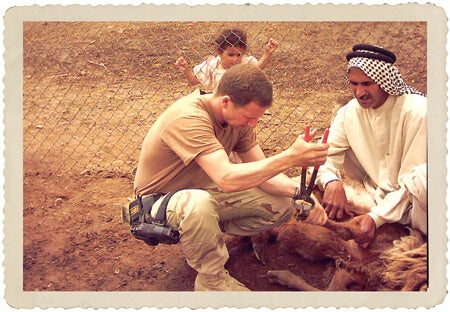

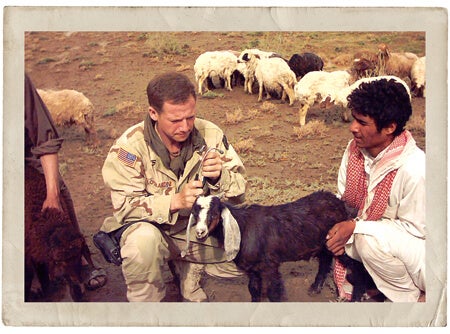

In 2003, Lombardini was given a mission in Kuwait, entering Iraq immediately after the start of the invasion and becoming one of the first conventional veterinarians in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Stationed in An Nasiriyah in the earliest days of the war, he and his team provided veterinary and public health support to more than 75,000 coalition soldiers, airmen, and marines, as well as food inspection services for the local Iraqi population.

Following his Iraqi tour, Lombardini was sent to the Aviano Air Base veterinary services in Northern Italy. The only U.S. Army member assigned to the Air Force base, he was officer in charge of zoonotic disease prevention, public health measures, and clinical care for the companion animals of thousands of active and retired service members and their families, as well as three populations of military working dogs. On top of this, he conducted vendor food and water inspections across Northern Italy, Hungary, Romania, the Balkans, and Western Africa.

At the same time, Lombardini supported NATO forces in Kosovo and Bosnia, giving medical support to military working dogs.

After Italy and before landing in his leadership role at AFRIMS, Lombardini would go on to work in different areas of the DOD’s complex and vast medical research and public health infrastructure. He completed a veterinary pathology residency at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and led field research projects in multiple countries. As a lieutenant colonel, he was selected to command the battalion responsible for the U.S. Army public health mission across much of the western half of the U.S. He attended the U.S. Army War College and conducted field research in the Arctic Circle and elsewhere, earned a PhD in Microbiology from the Open University through collaborative malaria work with Oxford University, and published in more than 80 peer-reviewed journals.

“I’ve had a fascinating career, some of it in very heated places,” he reflected. “A number of missions were a blend of animal care, human food safety, and infectious disease monitoring, like Operation Iraqi Freedom, which involved leishmania surveillance, military working dog care, and food inspection. It’s been wonderful and at times very sobering.”

Engagements of the Nonmilitary Kind

58th Anniversary of AFRIMS.

Lombardini’s career narrative is about to become even longer when he retires from the military this fall and returns stateside to work in industry, taking a leadership role in pre-clinical development.

For all his accomplishments, the busy colonel finds time for less globally urgent but personally essential activities with his wife and 11-year-old son. “We love to travel and enjoy good food and wine — my wife is Italian, so of course, we drink a lot of Italian wine,” laughed Lombardini. He’s also a wildlife photographer and an amateur paleontologist, the latter, he said, much to his wife’s chagrin.

Not bad, for a would-be diplomat, who confesses to having never been a great science student. “I certainly will not go down in history as a stellar student, but I was enthusiastic and my mentors recognized something in me and took a chance,” he said.

The gamble, for sure, paid off.

More from Bellwether

In the Office with Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM

Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM, shares her New Bolton Center office with the campus’s microbiology reference library.

Breaking New Ground: Penn Vet Builds Future-Ready Learning Hub

Set to open in the coming months, the 11,800-square-foot clinical skills center will be the first dedicated classroom space on the Kennett Square campus, ushering in a new era of…

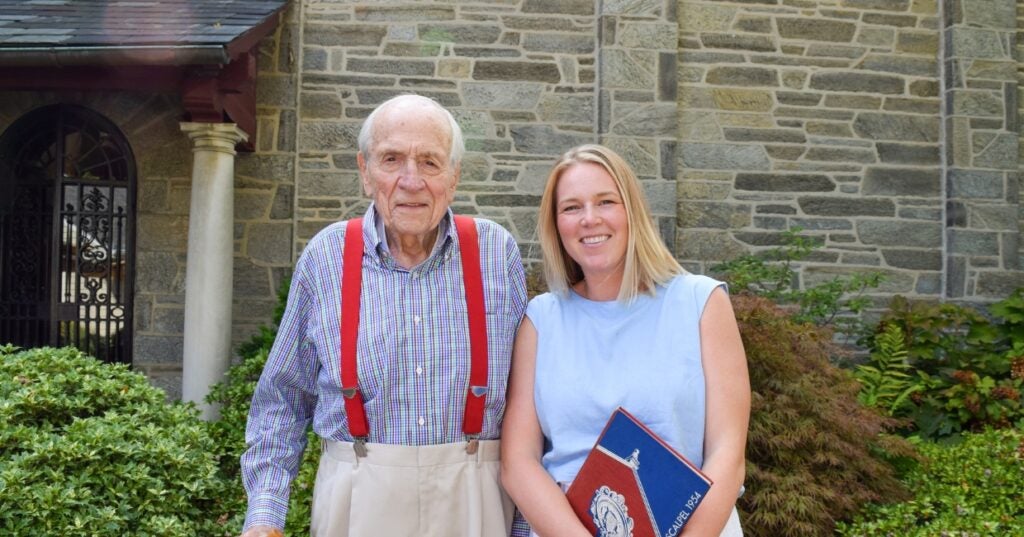

A Love of Animals and the Land

The Penn Vet of Dean Snyder, V’54, was a very different place than today. So was the world.