Bellwether Magazine

Discover Bellwether, Penn Vet’s premier biannual publication. Explore exciting stories and insights, and don’t miss the chance to delve into our extensive Bellwether Archives!

Featured Article

One Tiny Dog’s Outsized Contribution to Brain Surgery

Geddy Lee has lived a big life for a little dog.

Featured Articles

Penn Vet Holds Ribbon Cutting for New $2.8 Million Richard Lichter Advanced Dentistry and Oral Surgery Suite

The University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) commemorated the official re-opening of the newly named Richard Lichter Advanced Dentistry and Oral Surgery Suite at Ryan Hospital with…

From Bird Fractures to Human Shoulders

As a child in Central Pennsylvania, Stephen Peoples, V’84, loved science and the natural world.

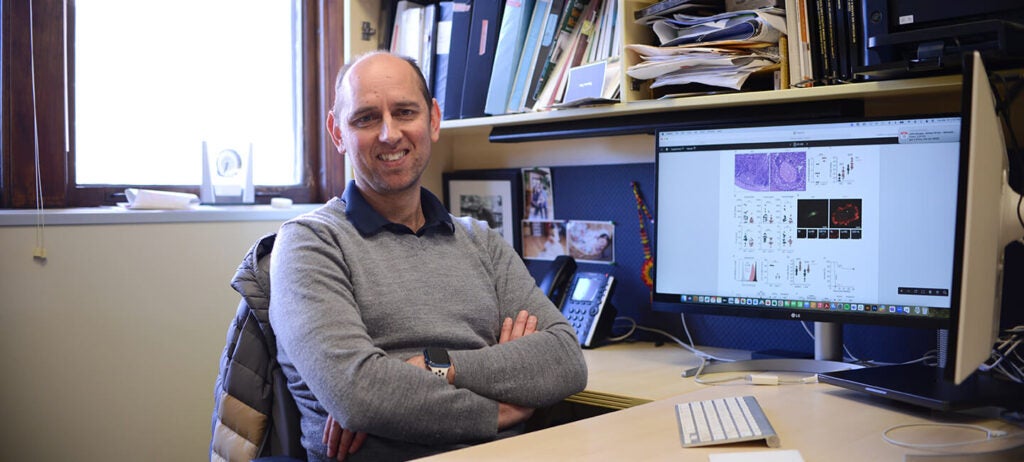

In the Office with Igor Brodsky, PhD

In his Philadelphia-based lab, Igor Brodsky is on a mission to understand how the body recognizes and responds to invading organisms that cause several diseases.