Educating a 21st-Century Veterinarian

In early 2022, Alexis Massey, V’26, voluntarily withdrew from her first year at Penn Vet for family reasons. She returned a year later to a radically transformed learning experience. Penn Vet’s new curriculum had launched for the Class of 2026 and those to follow.

Gone were the long hours of siloed didactic lectures on core information. In their place were shorter, integrated learning blocks with lectures and hands-on activities focused on animal health and disease and critical, independent, and scientific thinking.

“My first go ’round was lab after lab and hours of sitting and listening,” said Massey. “The content and exams focused mostly on one subject, with little overlap or larger context. This year, everything is much more integrated and dynamic. I’m loving it!”

The Evolution of Excellence

Penn Vet’s last major curriculum change was in the 1970s, when the School introduced a core/elective model. Subsequent years brought new additions and refinements, but nothing close to the magnitude of the 2023 overhaul.

Although innovative at the time, the old curriculum couldn’t keep pace with a changing world.

Discoveries in basic science and their translation into clinical treatments happen exponentially faster than 50 years ago. Technologies and wearable devices continue to transform education and medicine almost every day. And new understandings of adult learning and student and teacher needs have led to pedagogical innovations that better engage everyone.

“All of this means, we must prepare a different kind of graduate,” said Dr. Kathryn E. Michel, associate dean for education and professor of Nutrition. “The current rate of biomedical discovery means that even over the course of a veterinary education there will be new diagnostic capabilities and treatments when a student graduates that didn’t exist when they began school, so we must educate and cultivate lifelong learners.”

In other words, teaching students how to think rather than simply what to know is the purpose of today’s veterinary education.

Working Backward

In 2017, Michel, building on an effort begun by former Associate Dean of Education Dr. Tom Van Winkle, convened a redesign team to identify and implement a curricular model for 21st-century veterinarians.

“A group of dedicated and talented staff and faculty from across disciplines came together and said: ‘let’s do this right,’” said Dr. Amy Durham, assistant dean for education and professor of Anatomic Pathology. “We also enlisted the help of outside advisors and did a tremendous amount of research. What shook loose was CBVE.”

A Fixed Lens on Wellness & Diversity

Wellness

Penn Vet’s new curriculum explicitly addresses well-being to ensure graduates can recognize their own and their & colleagues’ stress and its sources. Students learn to engage in self-care, recognize when professional support is appropriate for themselves or others, and remedy adverse situations.

Diversity

Diversity is an essential part of Penn Vet’s mission and core to educating students who live and work in a diverse world. The new curriculum prepares future veterinarians to help build a more equitable and inclusive veterinary profession and to serve diverse communities with respect and empathy and without bias and discrimination.

Created by the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges (AAVMC), CBVE is competency-based veterinary education, an outcomes- based, learner-centered framework. Its mission, as defined by the AAVMC, is “to prepare graduates for professional careers by confirming their ability to meet the needs of animals and the expectations of society.”

“CBVE is modeled on the principle of backward design in education,” said Michel. “It starts with a desired endpoint or outcome — the characteristics, skills, and knowledge we want students to graduate with — and works backward to create a road map for getting there. We are beholden to our students, clients, patients, and other key stakeholders that we graduate competent practitioners and scientists, and in a traditional curriculum there isn’t really a way to evaluate competency in all areas. We can teach a lot of information and give high stakes examinations that show content mastery, but that doesn’t mean the abilities — the competencies — to practice in a safe way are there.”

So, Penn Vet’s curriculum redesign team started at the end and looked to the AAVMC CBVE framework’s nine domains of competency. To be practice ready after four years, Penn Vet students would need to exhibit competency in clinical reasoning and decision-making, individual animal care and management, animal population care and management, public health, communication, collaboration, professionalism and professional identity, financial and practice management, and scholarship.

From there, the group restructured, integrated, and streamlined material from the old curriculum into a format designed to maximize long-term retention of core material. At the same time, they incorporated new courses, teaching techniques, and technology to prepare students for all facets of veterinary medicine.

Learning, Block by Block

When Massey started last fall, her schedule looked very different than a year earlier.

Instead of individual classes on subjects like gross anatomy, neurosciences, and physiology, years one and two are now organized into blocks focused

on biological processes: Movement & Support; Digestion & Metabolism; Circulation & Respiration; Elimination & Detoxification; Defense & Barriers; Cognition, Senses & Response; and Reproduction & Development.

“We’re still giving didactic lectures with excellent information, but the content has been trimmed to core knowledge based on the backward design process,” said Durham. “This enables us to offer more labs, hands-on experiences, and asynchronous and group activities with clinical case integration. Students spend roughly the same amount of time learning every week, but the active learning opportunities give the sense of a lightened schedule, which we hope translates into better wellbeing.”

In year one, students learn about Animals in Health, delving into the form and function of healthy animals. Year two will build on this, presenting the same blocks through the lens of Animals in Disease, looking at prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

“This holistic approach toward each animal system is powerful,” said Dr. Elizabeth Woodward, clinical associate professor, Biomedical Sciences. “They learn the anatomical terminology of a particular system, as well as the histology and physiology that go along with it, and the interconnection between all of these. It’s really helping students understand how an entire system works. The old curriculum was more limiting because it taught anatomy, histology, and physiology in isolation of each other.”

When they launch in 2025 and 2026, the clinical blocks in years three and four, respectively, will be organized in three-week segments, during which students work in the clinics with faculty. Interspersed throughout are elective classroom and lab blocks that let students explore areas of interest.

At the beginning of each semester, students receive a foundational toolkit with background about material covered in upcoming blocks. And at the end of each semester, a capstone period provides them with an opportunity to apply and integrate information learned in preceding blocks.

Additionally, two “ribbon courses” thread throughout the first and second years. The Hippiatrika: Becoming a Veterinary Clinician focuses on professional development and clinical skills and gives newer students exposure to real patient cases in the clinic. And Of Clouds and Clocks: Becoming Veterinary Scientists emphasizes the principles of scientific inquiry and critical thinking skills.

The Ribbon Courses

The Hippiatrika

Becoming a Veterinary Clinician

This course is named after one of the earliest collections of writings on veterinary medicine from the fifth and sixth centuries. The Hippiatrika covers aspects of professional development not included

in the study of animal systems and diseases and incorporates labs that teach essential clinical skills and provide early exposure to clinical practice.

“The course provides the building blocks to train excellent veterinary clinicians. It focuses on veterinary-specific skills, such as physical examinations, diagnostic tests, animal handling, principles of population medicine or surgical skills, but also emphasizes skills relevant to all professionals and humans such as communication, welfare, reasoning, ethics, or diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

Dr. Cristobal Navas de Solis

Course organizer with Dr. Jennifer Huck

Of Clouds and Clocks

Becoming a Veterinary Scientist

Named in honor of 20th-century philosopher Karl Popper, who introduced the concept that every scientific theory is falsifiable. Of Clouds and Clocks covers principles of scientific enquiry, hypothesis- driven research, applied statistics, and epidemiology, and emphasizes using high-quality evidence to optimize clinical decision-making.

“Throughout the yearlong, active-learning course students develop skills in literature searching, interpretation, statistics, clinical decision-making, productive skepticism, and tolerance for ambiguity. One hallmark of a VMD is their ability to practice high-level medicine based on the best available evidence, and this course empowers our students to do so.”

Dr. Stephen Cole and Dr. Susan Bender

Course organizers

“Coming to vet school, I hoped there were going to be classes like these that discuss the nonclinical aspects of being a veterinarian,” said Kiera Zimmerman, V’26. “Learning animal science is so important. But it’s just as important to know how to communicate with clients and to understand biases, among other ‘soft subjects.’ This is all part of being a veterinarian.”

She added about The Hippiatrika’s clinical component, “I can’t say enough about how great it is! The lectures are hard, and Hippa is a good reminder of what I’m working for and why. Being with animals and applying classroom learning in real-life situations refreshes me for getting back to my studies and having it all make sense.”

One Year Down

As enthusiastic as new students are about the curriculum, “the reality is, change is hard,” said Durham. It’s taken some time to socialize faculty and staff to new ways of doing things.

“The Penn Vet community and many of our stakeholders value the School as a research institution; we have a very strong DNA in terms of scholarship,” said Michel. “Some initial resistance to change came from a concern that we’re turning our backs on what Penn Vet is known for and shifting the emphasis from a solid foundation in the basic, foundational sciences to a clinical curriculum. The redesign team was careful in our planning to account for this, and we’re working hard to ensure it doesn’t happen.”

It also helps that students and faculty, who are queried about their courses, present insights into areas and opportunities for improvement. And Penn Vet curriculum administrators meet with student focus groups from each course to gather input. The data collected from evaluations inform refinements in content, delivery, and assessments.

And any reported hiccups are expected, said Zimmerman, who appreciates that students have a role in smoothing them out.

“Our input is so valued, and it’s exciting to help everything take shape,” she said. “I chose Penn Vet for its excellence and innovation and trust the School to do what’s best for students and the profession. So far, so good!”

Our Curriculum Committee | |||

|

We thank the redesign team and acknowledge their time and effort enhancing Penn Vet’s curriculum. Below are the faculty and staff who spent countless hours re-engineering our student learning experience. A number of them gathered for a photo at last fall’s curriculum launch celebration. | |||

Redesign Team |

Block/Course Leaders | ||

| Kathryn Michel | Michelle Abraham | Olena Jacenko | Michael Povelones |

| Associate Dean for Education | Gary Althouse | Anna Kashina | Enrico Radaelli |

| Amy Durham | Jorge Alvarez | Mary Lassaline | Virginia Reef |

| Assistant Dean for Education | Michael Atchison | Christopher Lengner | Erica Reineke |

| Jennifer Punt | Susan Bender | Frank Luca | Dean Richardson |

| Associate Dean for One Health | Leontine Benedicenti | Timothy Manzi | Mary Robinson |

| Montserrat Anguera | Charles Bradley | Elizabeth Mauldin | Mark Rondeau |

| Associate Professor, Biomedical Sciences | Christine Cain | Katherine Mauro | Pascale Salah |

| Rose Nolen-Walston | Candace Chu | Michael May | Patricia Sertich |

| Associate Professor, Large Animal Medicine | Stephen Cole | Megan McClosky | Deborah Silverstein |

| Kathryn Rook | Jolie Demchur | Andrew Modzelewski | Carlo Siracusa |

| Assistant Professor, | Len Donato | Ariel Mosenco | Caroline Sobotyk |

| Clinical Dermatology and Allergy | Julie Engiles | Ali Nabavizadeh | Louise Southwood |

| Elizabeth Woodward | Erick Gagne | Cristobal Navas de Solis | Raymond Sweeney |

| Clinical Associate Professor, | Kristin Gardiner | Cynthia Otto | Jason Syrcle |

| Biomedical Sciences | Nancy Gartland | Mark Oyama | Charles Vite |

| Jessica Marcus | Anna Gelzer | Eric Parente | Koranda Walsh |

| Core Curriculum Director | Rebecka Hess | Meghann Pierdon | Brittany Watson |

| Dan McCall; | Andrew Hoffman | Martina Piviani | Kathryn Wulster |

| Curriculum Coordinator | Jennifer Huck | ||

More from Bellwether

From Bird Fractures to Human Shoulders

As a child in Central Pennsylvania, Stephen Peoples, V’84, loved science and the natural world.

In the Office with Igor Brodsky, PhD

In his Philadelphia-based lab, Igor Brodsky is on a mission to understand how the body recognizes and responds to invading organisms that cause several diseases.

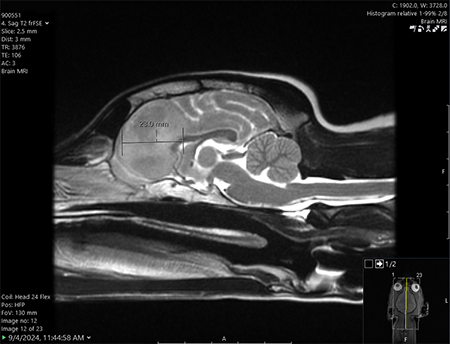

One Tiny Dog’s Outsized Contribution to Brain Surgery

Geddy Lee has lived a big life for a little dog. As a puppy, the tiny terrier mix was abandoned in Mississippi during a high-speed car chase. Rescued by law…