Copper’s Jaw-Dropping Experience

What’s better than a week away from it all? Parents. Kids. Dogs. Nothing but together time on an island accessible only by ferry. Just what the Weisman family planned for their summer 2023 vacation. But life had other plans.

Every summer, Ainsley and Ken Weisman, their children, Ryan and Leah, and their four dogs drive nine hours from their home in

Connecticut to Ocracoke, a little island off the coast of North Carolina. Last July, they had a new member on the trip: Copper, a three-month-old Goldendoodle who’d joined the family a month earlier.

“We got Copper for Ryan on his 12th birthday,” said Ainsley. “He’s our fourth dog and the family baby.”

The trip started off idyllic.

One dog walk changed everything.

“I was walking the dogs and heard something behind me. I turned around; an unleashed dog was coming toward us,” said Ainsley.

“I thought to myself, don’t overreact, stay calm; it’s probably going to

be fine.”

And it was. At first.

“The loose dog sniffed our older girls with mild curiosity then got to Copper and just sort of set in on him.”

After a few chaotic minutes, the attacking dog ran away. Ainsley and Ken assessed the damage. It was bad—Copper’s jaw and tongue hung loose from his little face.

Fortunately, there was a veterinary practice on the island. “We put a terrified Copper into our truck and drove to the clinic,” Ainsley said.

The island vet provided pain meds, wrapped the broken jaw, and sent the family to an off-island surgical hospital, an hour-and-a-half ferry ride and a drive of equal time away. “It was one of the longest days of my life.”

He’s just a baby. Please try.

By the time they reached the mainland hospital, “Copper was starting to decompensate,” said Ainsley. “My husband’s a physician, I’m a physician assistant, and we saw the signs. It was terrifying to see this little guy struggle so hard.”

The news was bleak. “His care team was candid and said it didn’t look good,” Ainsley said. “They asked if we wanted them to try everything. We said, ‘Yes, he’s just a baby; please, please try.’”

The hospital’s surgeons placed two plates to stabilize Copper’s mandible, and he was hospitalized for a few nights before heading home.

During the nine-hour drive to Connecticut, Copper had a feeding tube, and the family administered morphine. “He was such a little fighter,” Ainsley said.

As each day passed, the Weismans had more hope for his survival. But Copper hadn’t yet been to a dental specialist, and his regular veterinarian recommended specialty care. “She told us to go to Penn Vet,” said Ainsley.

So, a few weeks after the attack, Copper and Ainsley were back in the car. Ryan joined them.

What lies beneath

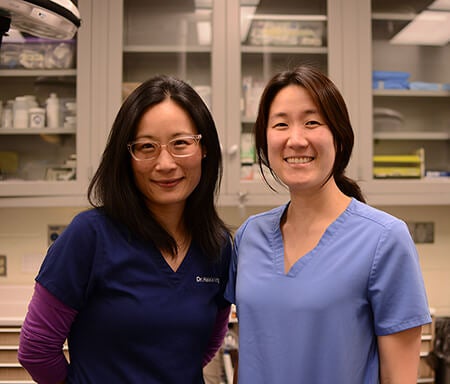

At Penn Vet’s Ryan Hospital, Esther Choi, DVM, a dentistry and oral surgery resident, led Copper’s exam.

“We weren’t too alarmed by anything,” she said, noting that the puppy was very lucky to have received treatment immediately after the attack.

“His teeth had come in a little bit weird, but that’s to be expected with trauma to a young jaw. This can result in malocclusion—when teeth don’t quite line up on the upper and lower jaws. Really, by the time we saw Copper, he was at an age where his teeth should have come out fully and been sitting correctly in the mouth.”

Choi and the team were concerned about the risk of periodontal disease: “Having teeth at different angles and not in the appropriate place predisposes the teeth and oral tissues to periodontal disease, which can lead to more serious problems down the road.”

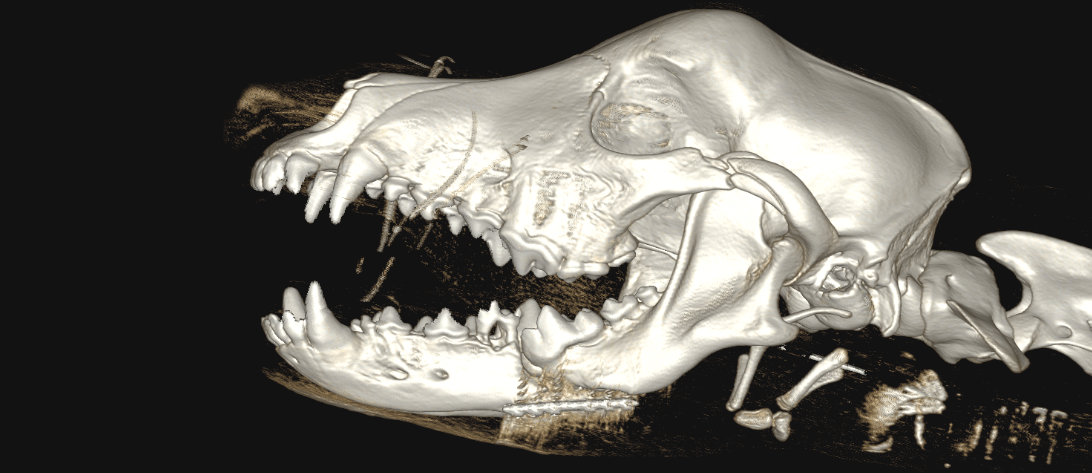

Choi scheduled Copper for an anesthetized oral exam, dental X-rays, and a CT scan for a more thorough look at his mouth. “What we see externally in the oral cavity is only the tip of the iceberg because most of the tooth structure lies underneath.”

Seeing the root of the problem

Ainsley, Ryan, and Copper returned to Ryan Hospital in October.

“We saw on the CT scans that he needed further treatment to correct jaw instability,” Choi said.

A multidisciplinary team of specialists from Penn Vet’s dentistry and oral surgery, radiology, anesthesia, and nursing teams prepped to repair the jaw.

First, they removed the original plates which, said Choi, “helped him heal as well as he had,” and placed an interdental splint to align loose jaw fragments and stabilize the young jaw.

Using a restorative procedure called vital pulp therapy, the team turned to saving one of Copper’s teeth. The therapeutic approach aims to preserve a tooth structure rather than completely extract it.

“There was one big molar that was weirdly angled, and we saved half of it to provide anchorage for the splint,” Choi said.

Imperfect alignment stresses the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) that connects the jawbone to the skull, so improving stabilization by removing the plate and having the bone heal itself is ideal. “In the long run, he’ll have less of a risk of developing osteoarthritis of the jaws and periodontal disease,” said Choi.

The calm—challenging—road to recovery

Copper sailed through surgery, and his healing is on track. But the family now faces another challenge: keeping a lively puppy relatively still during recovery.

“He’s not even a year old, and he has to stay calm,” said Ainsley. “No playing with the other dogs or running in the yard. Ryan and I have been walking him up to 10 miles a day to help work off some energy. Until a few weeks ago, he couldn’t even have a soft toy to chew. Imagine how hard it is for a puppy!”

But she has no regrets, and the family is excited to slowly start integrating Copper into the pack as he gets stronger.

“I feel fortunate to have had access to Penn Vet’s dental expertise,” she said. “We sometimes wondered if we did the right thing by putting him through all this. Should we have considered euthanasia? But this worked out well, and Penn Vet made it happen—at every point, Copper’s dental care team reassured us that he had every chance of healing and having a healthy, happy life.”

A field for the future

By all accounts, Copper received excellent care where and when he was attacked, but the Weismans’ regular veterinarian knew he would need specialized dental care for the best possible outcomes.

As the first veterinary school in North America to offer an organized veterinary dentistry and oral surgery program, Penn Vet has pioneered the field for nearly half a century. In 1989, it established one of the first veterinary dentistry and oral surgery residency training programs nationwide. The School remains one of the few U.S. vet schools with a strong curriculum in the specialty and a wide variety of clinical cases in dentistry and maxillofacial surgery.

“Our dental and oral surgery service is sought by clients from across the nation and attracts the finest residents from around the world,” said Brady Beale, VMD, DACVO, hospital director and chief medical officer at Ryan Hospital.

The service sees roughly 700 cases annually, and a robust clinical research program focuses on preventing dental disease and optimizing patient care. It’s set to expand with a new services suite that’s coming soon. (See sidebar.)

“I’m grateful to do my residency in facilities with such progressive, hardworking, intelligent individuals in so many different fields,” said Choi. “Penn Vet offers amazing niche services and has all these specialists across different disciplines collaborating on cases. It’s an exciting, interesting place to work in dentistry, especially given Penn Vet’s game-changing history.”

Time will tell, but Copper’s case may have inspired a future veterinary dentist. Ryan Weisman, who insisted on accompanying Copper on every visit to Penn Vet, said to his mom on one trip home, “I might want to be a vet. It seems really cool.”

Dentistry’s Future Cutting-Edge Space

This spring, Penn Vet will begin renovating and expanding its dentistry and oral surgery suite. The space will be called the Richard Lichter Advanced Dentistry and Oral Surgery Suite at Ryan Hospital after its namesake, a longtime philanthropic partner of the School.

When completed, the state-of-the-art clinic for comprehensive oral and restorative small animal patient care, clinical instruction, and clinical research will feature more dentistry and oral surgery stations, helping to shorten wait times and offer care to more patients.

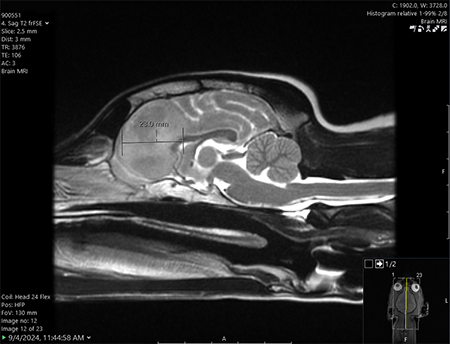

Additionally, a new cone-beam computed tomography system will significantly enhance clinicians’ diagnostic imaging ability to plan for complex surgeries, like cleft palate repair, oral tumor removal, and maxillofacial trauma surgery. And the imaging technology’s proximity to nine other surgery suites will provide more efficient care for other surgical patients, such as in neurology and orthopedics.

Along with enabling Ryan Hospital to accommodate more dental patients, the suite will serve as an arena to further clinicians’ understanding of various oral diseases and conditions, including cancers in the head and neck.

“I have witnessed firsthand the role Penn Vet veterinarians play in saving the lives of animals who come to Ryan Hospital in dire circumstances,” said Richard Lichter, who, in 2018, helped establish the Richard Lichter Emergency Room at Ryan Hospital. “It was natural for me to want the hospital to have the most modern and state- of-the-art dentistry and oral surgery capabilities.”

More from Bellwether

From Bird Fractures to Human Shoulders

As a child in Central Pennsylvania, Stephen Peoples, V’84, loved science and the natural world.

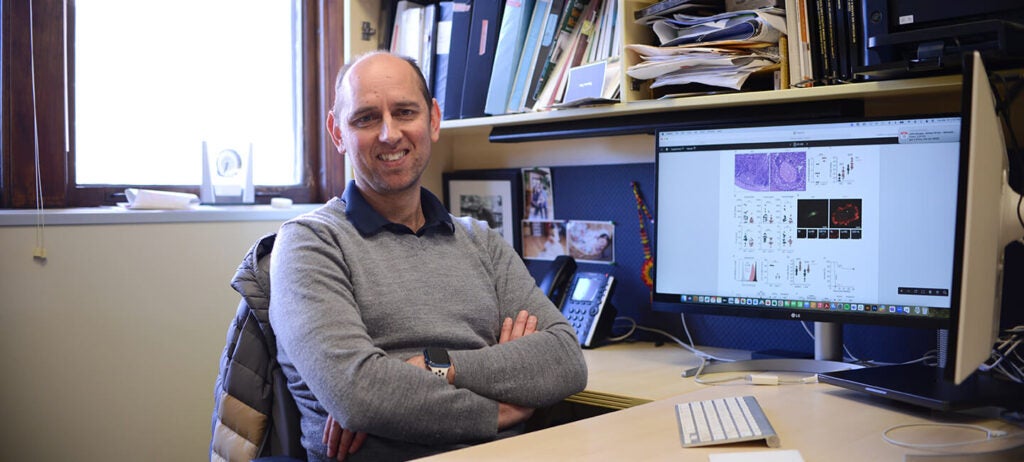

In the Office with Igor Brodsky, PhD

In his Philadelphia-based lab, Igor Brodsky is on a mission to understand how the body recognizes and responds to invading organisms that cause several diseases.

One Tiny Dog’s Outsized Contribution to Brain Surgery

Geddy Lee has lived a big life for a little dog. As a puppy, the tiny terrier mix was abandoned in Mississippi during a high-speed car chase. Rescued by law…