Triumph over a Twisted Fate

From the beginning, there was something special about the newborn Standardbred filly — and it wasn’t just that her muzzle twisted 45 degrees to the right.

She was born with an extreme facial deviation clinically known as wry nose. One of her nostrils was completely closed, making it nearly impossible to nurse and challenging to breathe comfortably. But she didn’t seem to notice. Her owner Matthew Morrison of Morrison Racing said the newborn won over humans and horses alike as she snuggled her dam and cheerfully greeted the people who helped her enter the world.

Still, the response to wry nose is often euthanasia.

“Wry nose can lead to significant issues with nursing and breathing,” said Kyla Ortved, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVSMR, Jacques Jenny Endowed Term Chair in Orthopedic Surgery and professor of large animal surgery explained. “Without surgical correction, a foal’s quality of life is very compromised.”

But Morrison and his daughter wanted to give their filly a chance to thrive.

“There was a fight in her. She didn’t know she was ‘abnormal.’ She just knew she needed to feed and was persistent,” Morrison said. “Without that fighting spirit, she probably wouldn’t have survived that first weekend.”

Fittingly, the Morrisons nicknamed her Wry Not and sent her from their stables in Indiana, Pennsylvania, to Penn Vet’s New Bolton Center. Ortved and a team of multidisciplinary specialists were waiting to give her a shot at a long, healthy life.

A case like no other

Wry nose is uncommon, especially cases as severe as Wry Not’s. Ortved and Jose Garcia-Lopez, VMD, DACVS, DACVSMR, associate professor of large animal surgery, have each seen only three cases in their extensive careers. Wry Not’s stood out.

“It was a severe deviation, the worst I’ve ever seen,” Garcia-Lopez said. He added that surgery was a consideration, although the location of the bend would make it more complicated.

But before any surgical intervention, “it was important to ensure Wry Not was in excellent systemic health,” said Michelle Abraham, BSc, BVMS, DACVIM, assistant professor of clinical critical care medicine.

The moments after birth are critical for any young animal. In the first few hours, mothers pass vital antibodies to their offspring through colostrum — or “first milk.” Because Wry Not struggled to nurse, her clinical team was concerned she lacked the immunity needed for a major procedure.

“Any local infections could have disastrous effects on the outcome,” Abraham said.

Complicating matters even more, an ultrasound of Wry Not’s lungs revealed pneumonia.

Abraham’s team immediately started Wry Not on antibiotics and installed a feeding tube to supply supplemental colostrum and hyperimmunized plasma.

“Antibiotic therapy and continued nutritional support were important for her to grow strong enough for surgery,” she explained.

A precision procedure for a precious patient

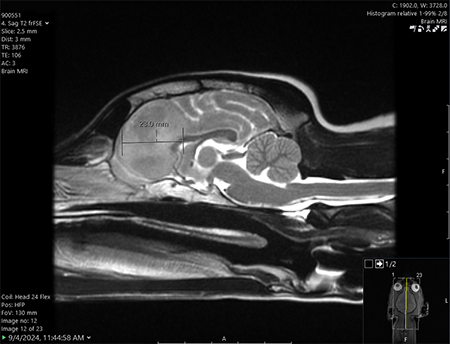

After roughly a month of medication and observation, Wry Not was ready for surgery. But first came imaging.

Two weeks pre-surgery, the care team scanned the muzzle of an anesthetized Wry Not using OmniTom, a mobile CT scanner that delivers high-quality, point- of-care imaging. The technology offered a 3D look at her head and deformity before surgery, aiding surgeons in planning their approach.

“There wasn’t a lot of room for error,” Garcia-Lopez recalled. “The surgery required precise measuring and careful cutting.”

Once they had a plan, they scheduled surgery.

On the day of the procedure, the New Bolton Center care team anesthetized the filly, who lay comfortably on her belly.

First, they resected Wry Not’s nasal septum to open her nasal passages. They then performed corrective osteotomies — or cuts in the bones — of her nasal and incisive bones to realign her nose. Finally, they put in a set of specialized plates to hold the nasal and incisive (which hold upper jaw teeth) bones in the correct position while she healed.

Wry Not’s life-changing — and life-saving—surgery took roughly three hours. Post-op, her care team was delighted to find the filly bright and alert.

“A case like this is very much a team effort,” said Ortved. “There’s everyone from the NICU that admitted her and kept her alive, an anesthesiologist who handled this difficult case, a radiologist, an equine dentist, and many other specialists, along with nurses, staff, residents, interns, and vet students.”

The recovery road from wonky to wonderful

Once Wry Not was stable enough for discharge, she was transferred to the care of Ashley Taylor, DVM, at Twin Ponds Farm, a rehabilitation center about 10 minutes from New Bolton Center.

A few weeks after surgery, the New Bolton Center team removed the specialized plates, and equine dentist Amelie McAndrews, DVM, DAVDC-Eq, a clinical associate at New Bolton Center, placed a bite plate on her lower jaw to encourage her upper jaw to grow straight out and not down. The bite plate will continue to be replaced over the first year of her life as the filly grows.

Today, Wry Not travels frequently between the farm and Penn Vet for regular check-ups and replacements of the bite plate.

She is a loving, if unusual-looking, horse. While she is now fully weaned and can enjoy grain, hay, and grass like any healthy equine should, her muzzle will never be “perfect.”

“With wry noses, we can make the upper jaw and nose straight, but the upper jaw will always be shorter than the lower jaw,” said Ortved.

The New Bolton Center clinicians fondly joke that, because of Wry Not’s one-of- a-kind looks, she is “a foal only a mother could love.”

“And a surgeon,” added Garcia-Lopez. “And me and my daughter,” said Morrison.

More from Bellwether

From Bird Fractures to Human Shoulders

As a child in Central Pennsylvania, Stephen Peoples, V’84, loved science and the natural world.

In the Office with Igor Brodsky, PhD

In his Philadelphia-based lab, Igor Brodsky is on a mission to understand how the body recognizes and responds to invading organisms that cause several diseases.

One Tiny Dog’s Outsized Contribution to Brain Surgery

Geddy Lee has lived a big life for a little dog. As a puppy, the tiny terrier mix was abandoned in Mississippi during a high-speed car chase. Rescued by law…