Bellwether Magazine

Discover Bellwether, Penn Vet’s premier biannual publication. Explore exciting stories and insights, and don’t miss the chance to delve into our extensive Bellwether Archives!

Featured Article

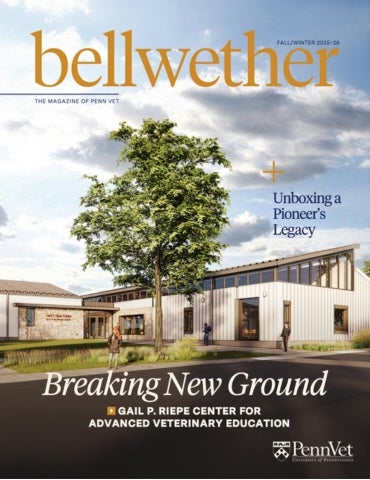

Breaking New Ground

Penn Vet Builds Future-Ready Learning Hub

Featured Articles

Unboxing a Pioneer’s Legacy

Born in 1919, Jane Hinton, V’49, came of age when opportunities for women in science and medicine were scarce — and for Black women, nearly nonexistent. expertise in poultry and…

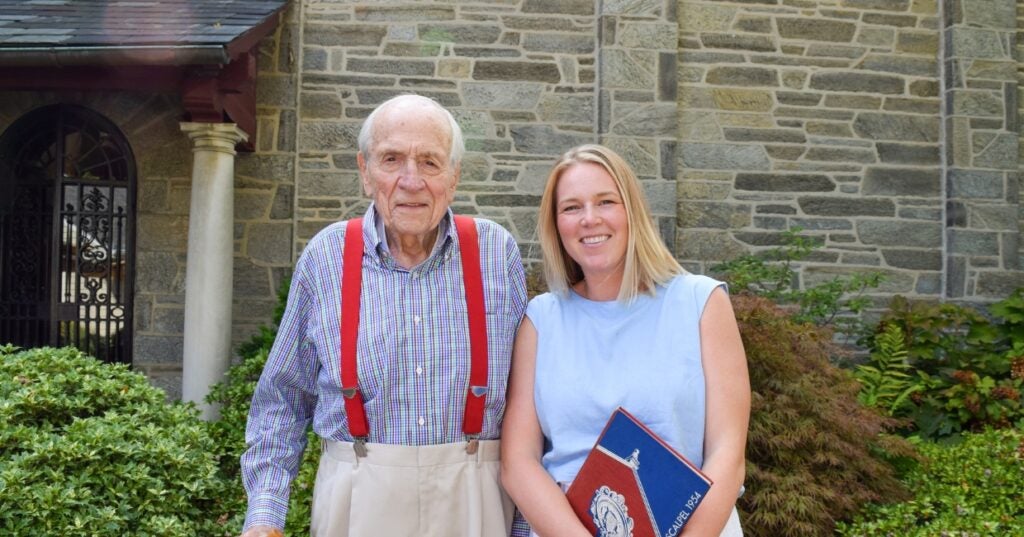

A Love of Animals and the Land

The Penn Vet of Dean Snyder, V’54, was a very different place than today. So was the world.

Comforting Philanthropy

At Penn Vet’s Ryan Hospital, world-class clinical care is matched with deep compassion for animals and the people who love them.

In the Office with Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM

Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM, shares her New Bolton Center office with the campus’s microbiology reference library.