Olive, the Tiny Little Fighter

2021 was an emotional roller coaster for the Martino family. First there was joy — Joe, his wife, and their three kids, ages 12, 10, and 6, welcomed a new puppy. Then despair: the puppy died from parvovirus. There was joy again with a new puppy named Olive. But despair soon followed when the four-month-old Shih Tzu mix became critically ill.

“We couldn’t believe it,” said Martino. “The kids were just starting to emotionally recover from the first experience. Now here we were again.”

On an otherwise normal Thursday afternoon, the family heard Olive crying from her hiding place under the sofa. She was breathing rapidly and had coughed up small droplets of blood.

“To our knowledge, she hadn’t done or eaten anything unusual,” said Martino.

Their primary care veterinarian ruled out toxicity and parvovirus, but chest X-rays showed fluid in Olive’s lungs — the clinical diagnosis is non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema — and air leaking from her lungs in her chest cavity. Called a pneumothorax, air surrounding one or both lungs can be a life-threatening condition that keeps the lungs from expanding and an animal from getting enough oxygen.

The veterinarian referred Olive to Penn Vet’s Ryan Hospital, where she would be one of 9,000 small animals to come through the hospital’s Emergency Services last year and one of 1,200 cases to receive intensive care.

The large, diverse caseload, advanced trauma and emergency services, intensive care unit (ICU), board-certified specialists and nurses specially trained in emergency and critical care veterinary medicine, and cutting-edge diagnostics make the West Philadelphia–based facility a first choice for companion animal owners across the region.

“We knew she would have the best chance of survival at Penn Vet,” said Martino, who was unable to get to Ryan Hospital in time to save their first puppy that died.

Dr. Selimah Harmon, an Emergency & Critical Care resident, was primary clinician on Olive’s case. She and supervising clinician Dr. Deborah Silverstein, professor of Emergency & Clinical Care, spoke about caring for Olive.

Q: Olive arrived at Emergency Services (ES) just in time. Those first hours were critical – and fraught with complications. How did you approach saving the life of this adored family puppy?

Silverstein: Olive was in severe respiratory distress by the time she got to ES. The team was limited in what they could do diagnostically because she needed oxygen and was placed in an oxygen cage. She remained on oxygen overnight and was transferred to the ICU in the morning. Her breathing remained labored even with extra oxygen.

When I met her in the morning, I knew her prognosis was grave unless we placed her on a ventilator. But the pneumothorax complicated her case. The pressurized air entering her lungs from the ventilator could cause further air leakage into her chest.

Harmon: Dr. Silverstein and I wanted to place a tube in Olive’s chest to remove air from around the lungs to help her breathe. But Olive was so little and unstable, we needed help inserting the tube while managing her medication and pain. We called on our surgical team.

Emergency room nurses, the surgical and ICU teams, and veterinary students all gathered around to help place the tube in her little body.

Unfortunately, Olive’s respiratory distress worsened. We were very concerned about her fatiguing and potentially not getting enough oxygen for her organs. So, we put her on the mechanical ventilator to relieve her distress and make sure her oxygen values were adequate.

Q: It was touch-and-go at first. Once you stabilized Olive, what else did you uncover? And how were you able to proceed?

Harmon: After we intubated her, Olive remained anesthetized. She received continuous infusions of medications to support her cardiovascular system and keep her asleep. Only then could we start to investigate the root cause of the pneumothorax and lung edema.

We took emergency chest X-rays and they showed increased air in the chest and fluid in the lungs compared to the ones taken earlier at the primary care vet. There was no fluid in her abdomen, chest, or around her heart. So, we focused on her respiratory distress.

Silverstein: Ultimately, her case is a bit of a mystery. We usually see non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema from instances of drowning or choking or toxins — when the dog tries frantically to breathe but there’s an obstruction in the airway. There was no obvious cause in Olive’s case. The owners didn’t witness anything, and they had been with her all day. Our prevailing theory is maybe she choked on something and ended up passing it but then suffered from complications.

Harmon: Throughout her two days, we made regular adjustments to her medications and ventilator settings. She spiked a fever at one point, and we worried about an infection so we started her on IV antibiotics.

By the third day, Sunday, she was showing improvement. Her fever resolved and lung functions were closer to normal. We took her off the ventilator and placed her back in the oxygen cage. By Tuesday, now the fifth day of her stay, she no longer needed oxygen support. The next day, on Wednesday, nearly a week after arriving at Penn Vet, Olive went home.

She came in for a follow-up a week later, and we were thrilled with her progress.

Q: One of the benefits of working alongside other specialists is immediate access to them in severe cases such as Olive’s. Can you tell us how you worked together for Olive?

Silverstein: It takes a lot of collaborative effort to get an animal like this stabilized for thorough diagnostics and appropriate treatment. The entire process is a well-oiled machine of fine tuning and close monitoring. We certainly benefit from onsite specialists, and Ryan Hospital also has excellent nurses that help with a lot of the critical support — managing infusions, monitoring pulse rates, watching for anything of concern.

Q: Olive was young and very, very little. What are some of the challenges of diagnosing and treating animals at such a vulnerable age?

Silverstein: From the second a juvenile animal enters the hospital, we have a different thought process with regards to diagnostics and treatments than we do with fully developed animals. At Olive’s age, things like cancer are much less likely, but underlying infection or the potential to pick up an infection in the hospital, when their vaccine status is in its infancy, are concerns.

Puppies have a high calorie requirement, so we must make sure they’re getting enough calories — we fed Olive through a nasogastric tube. And they need more fluids to stay hydrated.

Medication dosing in puppies is also a delicate balance. We want to be careful to give just the right amount of medication. Puppies are like little drug sponges — they need a lot of medication but not too much or it might cause damage. And there are drugs we just can’t use with them because of potential adverse effects on development. We need to account for all these things. It can be tricky.

Q: Tricky but worth it! In your careers, what have you learned about treating pediatric animals?

Silverstein: Young animal patients can be so resilient; they’re little fighters. If I have one motto for pediatrics, it’s don’t ever give up on a puppy or a kitten. They can have such amazing recoveries from what appears to be severe, life-threatening disease. These tiny animals will fight to survive if we can help them.

Harmon: Olive is a great example of a little dog with a mighty spirit and will to live. It was touch-and-go there for a while, but she pulled through.

More from Bellwether

In the Office with Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM

Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM, shares her New Bolton Center office with the campus’s microbiology reference library.

Breaking New Ground: Penn Vet Builds Future-Ready Learning Hub

Set to open in the coming months, the 11,800-square-foot clinical skills center will be the first dedicated classroom space on the Kennett Square campus, ushering in a new era of…

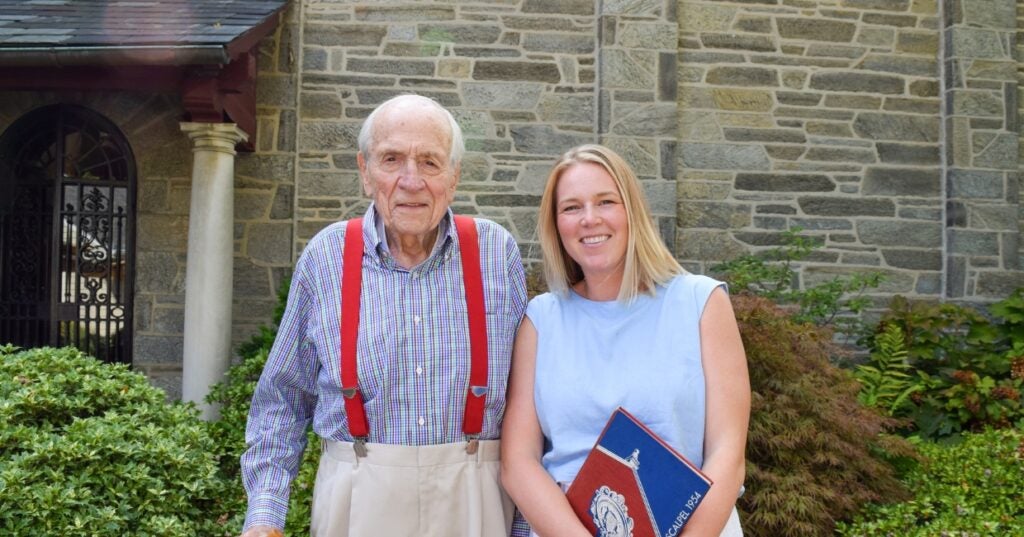

A Love of Animals and the Land

The Penn Vet of Dean Snyder, V’54, was a very different place than today. So was the world.