Penn Vet News

Featured News

Penn Vet’s Next Gen Biomedical Scientists Present Their Research at the Annual Veterinary Scholars Symposium

Two dozen budding Penn Vet scientists presented a rich array of ambitious biomedical research projects at the annual Veterinary Scholars Symposium held last month in Spokane, Washington.

A New Penn Vet Clinic Brings Support and Hope for Dogs with Retinal Disease

Zoey the cockapoo greeted life with tail-wagging joy. A mass of tawny curls, she loved everyone, and they loved her back.

Penn Today News

Keeping food safe and animals healthy (link is external)

A strain of the H5N1 virus—best known for causing avian influenza—was detected in U.S. dairy cattle for the first time in March 2024. It has since spread to more than…

Food waste: Recycling, not discarding, offers huge environmental benefits (link is external)

Researchers at Penn Vet examine how common food waste recycling methods, including composting, could have a big impact on greenhouse gas emissions and the use of natural resources.

Improving T-cell responses to vaccines (link is external)

Penn Vet and Penn Medicine researchers have modified mRNA vaccines to include the cytokine IL-12 and improve T-cell responses which could improve the body’s ability to fight infections.

In the Media

Bellwether Features

Penn Vet Holds Ribbon Cutting for New $2.8 Million Richard Lichter Advanced Dentistry and Oral Surgery Suite

The University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) commemorated the official re-opening of the newly named Richard Lichter Advanced Dentistry and Oral Surgery Suite at Ryan Hospital with…

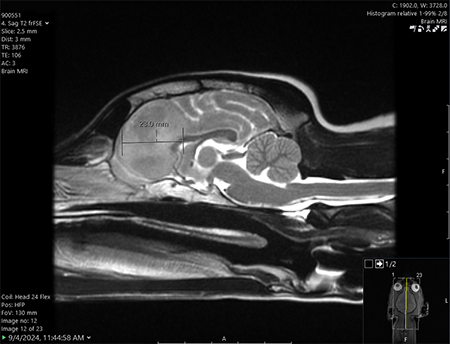

One Tiny Dog’s Outsized Contribution to Brain Surgery

Geddy Lee has lived a big life for a little dog. As a puppy, the tiny terrier mix was abandoned in Mississippi during a high-speed car chase. Rescued by law…

From Bird Fractures to Human Shoulders

As a child in Central Pennsylvania, Stephen Peoples, V’84, loved science and the natural world.

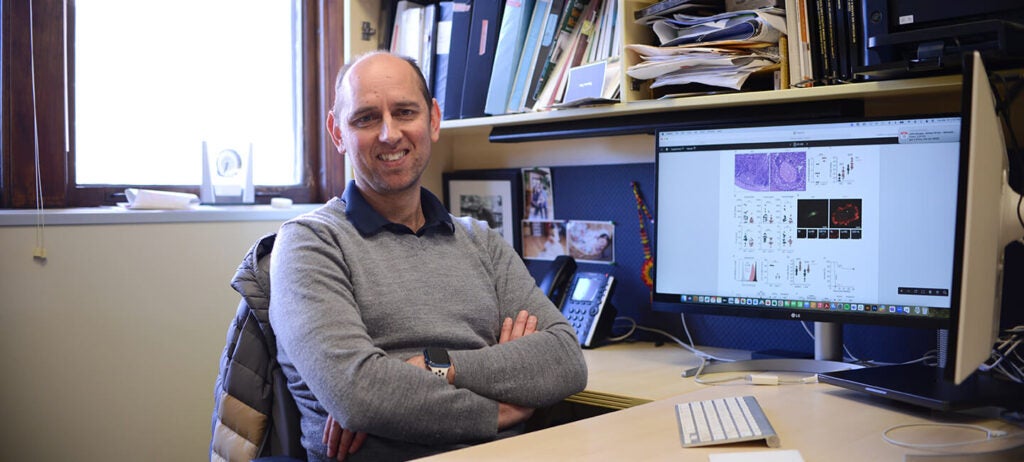

In the Office with Igor Brodsky, PhD

In his Philadelphia-based lab, Igor Brodsky is on a mission to understand how the body recognizes and responds to invading organisms that cause several diseases.

For the media

Press Inquiry

For all press inquiries, please the form below. This form is for media purposes only. If you are an animal owner, contact Ryan Veterinary Hospital for Companion Animals or, for our large animal hospital, New Bolton Center.

Non-News, Commerce-Affiliated Content Site Inquiries

The Office of Communications is selective in responding to requests from freelance writers on assignment for non-news, content building sites.

- All interviews with clinicians, faculty, staff and/or students in association with Penn Vet, Ryan Hospital, or New Bolton Center must be arranged through and facilitated by a representative from the Office of Communications. Please do not contact such individuals directly.

- When submitting a media or interview inquiry, please fill out this form. Include your name, contact information, and general details of your pitch including important deadlines.

- Visits to Penn Vet’s campuses and/or hospitals by members of the media must be arranged directly through a representative from the Office of Communications. For the well-being and privacy of our animal patients and their owners, a representative from the Office of Communications must also accompany any arranged visits.

- If an interview requires a Penn Vet clinician, faculty or staff member, or a student to be recorded on video, please be aware that a signed copy of the University’s video authorization form must be submitted to and confirmed by a representative from the Office of Communications prior to any taping. Additionally, an an Appearance Release must be supplied to the Office of Communications for review and approval prior to obtaining a signed agreement from the individual that is to appear on camera.