Our Research

Our research has involved studies on mammalian germ cells and early embryos. Initially, we developed a culture system and manipulation techniques for mouse eggs that are the foundation for subsequent mammalian egg and embryo experiments in the field, including nuclear transfer and in vitro fertilization of human eggs.

We then used these methods to show that mouse blastocysts can be colonized by foreign stem cells and result in chimeric adults, which led to the development of embryonic stem cells. Subsequently, we used these culture and manipulation techniques to develop transgenic mice. In recent years, our research has focused on male germline stem cells, and these studies demonstrated that spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) from a fertile male mouse can be transplanted to the testes of an infertile male where they will colonize the seminiferous tubules and generate donor cell-derived spermatozoa, thereby restoring fertility.

In addition, SSCs of mice and other rodents can be cultured in vitro and their number increased, and the SSCs can be frozen and preserved for long periods. The ability to culture, transplant and cryopreserve SSCs makes the germline of individual males immortal. The transplantation and freezing methods are readily transferrable to the SSCs of all mammalian species.

However, a culture system for SSCs of nonrodent species has proven to be difficult to develop, and published reports of success have not been independently confirmed and are not universally accepted. Therefore, in recent studies we have attempted to develop a reliable system to culture human SSCs, which is essential to preserve and expand for later use the SSCs of prepubertal boys who will receive germ cell destroying treatment for cancer.

As part of these studies, we are establishing the genes and regulating mechanism used by mouse and human SSCs to survive and replicate, which will contribute to the understanding necessary for human SSC culture and expansion. In the long term, a culture system will also allow the development of techniques to support SSC differentiation in vitro with production of spermatozoa capable of fertilizing eggs.

In addition, the SSC assay system provides a powerful technique in which to test the conversion of somatic cells to functional SSCs. Over the past 10 years, we and others have identified transcription factors and micro RNAs that play key roles in SSC self-renewal. In current research, we plan to use this information to reprogram somatic cells into germ cells, specifically SSCs. The transplantation assay provides an unequivocal conformation of this reprogramming for a single cell.

Moreover, it allows for the identification of gene activation during the differentiation process in vivo and production of progeny from sperm produced from reprogrammed cells. In the future, the approach could be used to address fertility problems in humans and possibly the correction of genetic defects.

This research is supported by grants from National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development and the Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation.

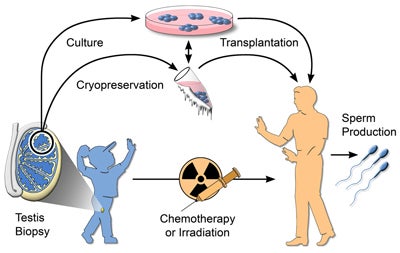

Male germline stem cell preservation

Before treatment for cancer by chemotherapy or irradiation, a boy could undergo a testicular biopsy to recover stem cells. The stem cells could be cryopreserved or, after development of the necessary techniques, could be cultured. After treatment, the stem cells would be transplanted to the patient’s testes for the production of spermatozoa. The critical roadblock to widespread clinical use of this approach is the absence of culture techniques.

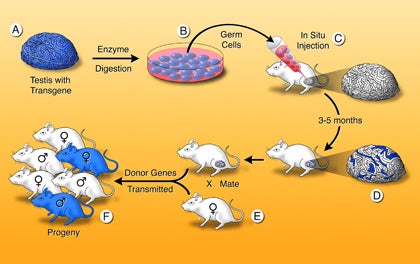

Testis spermatogonial stem cell transplantation method

A single-cell suspension is produced from a fertile donor testis (A). The cells can be cultured (B) or microinjected into the lumen of seminiferous tubules of an infertile recipient mouse (C). Only a spermatogonial stem cell can generate a colony of spermatogenesis in the recipient testis. When testis cells carry a reporter transgene that allows the cells to be stained blue, colonies of donor cell–derived spermatogenesis are identified easily in recipient testes as blue stretches of tubule (D). Mating the recipient male to a wild-type female (E) produces progeny (F), which carry donor genes. Genetic modification can be introduced while the stem cells are in culture.