A Love of Animals and the Land

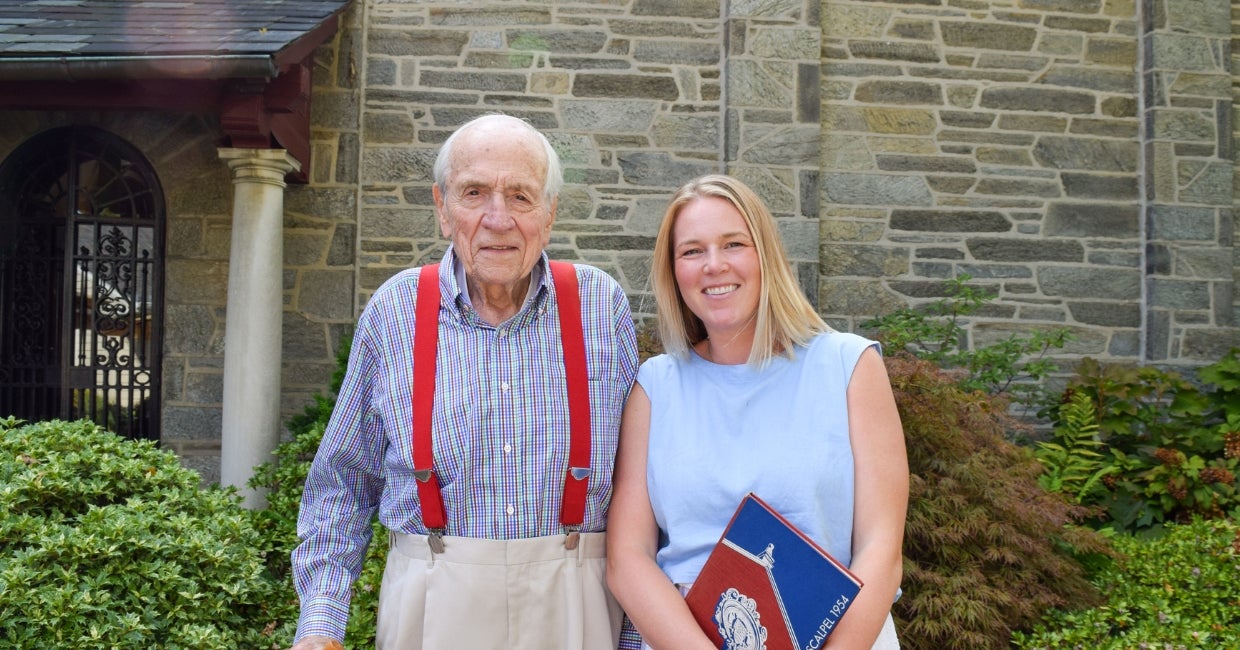

The Penn Vet of Dean Snyder, V’54, was a very different place than today. So was the world.

Back then, there were only two women in Snyder’s class. And Snyder, the son of Central

Pennsylvania farmers of modest means, would become one of the first graduates of the newly acquired New Bolton Center. Purchased in 1952, students arrived in 1953, and it was formally dedicated in 1954.

Not the developed campus of today, Snyder recalled the dairy and some stables, cattle, horses, and pigs. But the education Snyder received there was more than enough to kick-start a long, long career that led this country boy with a restless spirit and a curious mind across the states and beyond. He helped develop agricultural innovations still in use today.

“I had some good breaks during my time at Penn,” noted Snyder wryly, now 98.

He also inspired a family legacy — a devotion to animals and the land — that’s carried over generations.

“I was so inspired by his career path,” said Jane Annand, V’18, 36, one of Snyder’s grandchildren who is now a small animal veterinarian in Maryland. “I always wanted to be a vet, and I think it was because of him.”

When Annand graduated from Penn Vet, Snyder presented her with her diploma.

“I was very proud,” Snyder said.

Humble beginnings on a family farm, and meeting a country vet

It all started many years ago on Snyder’s family farm. As a boy, he helped his mother with the farm chores.

“We had a grocery route once a week, and we’d dress a lot of chickens for that,” Snyder said. “I

did some of the milking.” He also did the weeding, but without the aid of modern equipment. “I was the scythe guy,” he said, chuckling. “I just loved agriculture.”

Then one day, when the family mule sustained a dislocation injury, Snyder, still a teenager, made

an important acquaintance: a veterinarian.

The clinician, part of a local family of veterinarians, put the mule in a device that allowed him to heal. Snyder still recalls how impressed he was. It sparked his imagination.

“It was something I could aim for,” Snyder said.

As much as he loved farming, he didn’t see a future in it for him. The family farm was very small. As it was, he hitchhiked ten miles each way to high school. Money was scarce.

“I grew up during those Depression years,” Snyder said. “We’d get one pair of shoes a year, and as I outgrew them, I cut the toes out so I could wear the shoes. In summertime, I threw them away and went barefoot.

“In my senior year, an Army recruiter came in and gave us a pitch. I went up to him after his presentation, and I asked him if I joined the Army, could I get shoes every time I needed them? He said, ‘Certainly.’ So, I signed up.”

Snyder was shipped out to Europe. But the Army paid for education, too. Snyder got to earn his undergraduate degree, in the process meeting his wife, the stylish and whip-smart Agnes Marion

Millard, a fellow student at Lebanon Valley College. He would be called up again to serve during the Korean War. Through the G.I. Bill, he fulfilled his long-held dream: he entered the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine to become a veterinarian.

A Penn Vet student and the makings of an inspiring career

It was a different time in many ways. Women now make up the majority of Penn Vet students, and veterinary students in general. That was not the case in the 1950s. And in society at large, the second wave of the feminist movement was still years away.

During a recent interview, family members talked about how Marion, now 97, herself a force to be reckoned with who ran the household and raised the children while Snyder traveled for his career,

helped her husband get through all those difficult anatomy class memorizations.

Marion’s family had two large beef cattle operations, Millarden Farms in Annville and another farm in Georgia. After graduation, Snyder became the veterinarian for both, with access to a private plane to travel between the two. That continued for more than a decade, until the family decided to exit the business.

But soon a new door opened. Through colleagues from the Penn State Stockmen’s Club, Snyder

went to work for Eli Lilly. There he embarked on a long career in applied science, helping to develop the use of cattle breeding practices that are widespread today, such as estrus synchronization to allow more efficient use of artificial insemination, as well as vaccinations in poultry. Annand, his granddaughter, said that while she was an undergraduate at Colorado State University, she met ranchers who had worked with her grandfather while he was developing

his cattle breeding protocol many years before.

“It was a really cool moment for me,” Annand said.

Annand grew up listening to her grandfather’s stories about life on the farm.

“A lot of it was just so romantic,” she said. Like hearing about memories of Christmas mornings checking on the cows.

And while Snyder came from a time when men and women often had separate pursuits — females in the home, males out in the world — he didn’t treat his girl offspring that

way. Growing up, Annand recalled that she and a same-age female cousin were often their grandfather’s companions of choice on many adventures.

He was an avid bird watcher and beekeeper, and the girls shared in those forays. Annand’s curiosity led her to amateur autopsies on deceased woodland critters she found, just as her grandfather had done as a boy, and he certainly did not discourage her.

“And he always had stories to tell,” she said. “He always just had the best stories.” He always had dogs, too, she recalled. Mostly English springer spaniels. He trained them to be good bird dogs, and her grandmother taught them to behave in the house.

“I inherited his love of animals,” Annand said.

And while she’s the only grandchild to become a veterinarian, she said several of her siblings and cousins found careers in the sciences, and all inherited their grandfather’s love of nature and benefited from their grandmother’s sense of style and grace.

At the retirement community where the couple now reside, Snyder still enjoys the feel of the earth; he gardens regularly and takes daily walks — up to three miles a day. He walks with the aid of a cane he made himself. He still does woodworking.

Annand now has her own children. Although they are only three and 18 months, already she is passing down the lessons learned during her childhood, many from the times spent with her grandfather.

They know that puddles are to be splashed in, and that nature walks are times for exploring. She takes them to look for birds like those in their great-grandfather’s Audubon books. And they’re frequent visitors to the Chesapeake Bay that surrounds where they live. She says she wants their childhood to be like the one her grandfather helped give her.

Probably the most inspiring thing about my grandfather is just the fact that he’s always had this sense of wonder,” Annand said. “He always found something to be interested in.” That’s the legacy that lives on today.

More from Bellwether

In the Office with Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM

Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM, shares her New Bolton Center office with the campus’s microbiology reference library.

Breaking New Ground: Penn Vet Builds Future-Ready Learning Hub

Set to open in the coming months, the 11,800-square-foot clinical skills center will be the first dedicated classroom space on the Kennett Square campus, ushering in a new era of…

Unboxing a Pioneer’s Legacy

Born in 1919, Jane Hinton, V’49, came of age when opportunities for women in science and medicine were scarce — and for Black women, nearly nonexistent. expertise in poultry and…