Behind the Breakthroughs: Andrew Vaughan

Rewriting the Rules of Lung Repair

Penn Vet’s Andrew Vaughan pushes to uncover why some lungs rebound and others have lasting damage, and how to change that

Behind the Breakthroughs is a Q&A series that shines a light on the people and ideas driving discoveries across Penn Vet.

In this edition, we sit down with Associate Professor of Biomedical Sciences, Andrew “Andy” Vaughan, PhD. Vaughan is a molecular and cellular biologist with a specific interest in lung regeneration. He seeks to understand why certain patients fully recover from severe respiratory infections, while others face debilitating damage. Vaughan and his team are looking at how injured lung cells miscommunicate during recovery, thereby driving inflammation and fibrosis. They are also determining mechanisms that can prevent or even reverse this damaging process. Vaughan continues to advance his vital work while navigating the shrinking federal support for research, an obstacle that underscores the urgent need to support biomedical breakthroughs that are making our world a more curative and healthier place.

What big problem is your research aiming to solve?

Lung regeneration! In short, the lung sits in the middle ground of tissue repair: it’s much more regenerative than the brain or the heart, but much less regenerative than, say, the liver. An example of this is when people are hospitalized and intubated in the ICU after severe pneumonia from, for instance, influenza or COVID-19. Some of these individuals who survive recover to have completely normal lung function. Conversely, others deal with long-term, debilitating lung issues resulting from regenerative failures (e.g., scarring) in their lung tissue. We want to figure out how to prevent, or even reverse, these long-term consequences of severe lung injury.

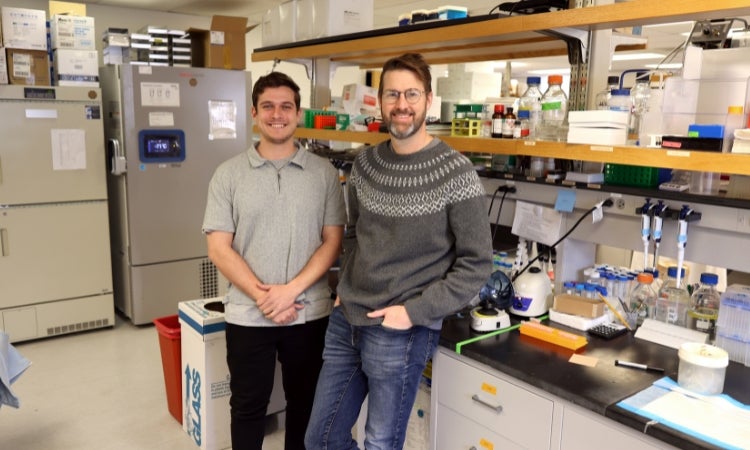

What is the flagship project that you are working on right now?

It’s really hard for me to pick one “flagship” project because the students and postdocs in my lab have their own projects that are all very exciting. Because I have to choose, I will highlight the work of an incredibly talented graduate student in my lab, Nick Holcomb. Nick was curious to understand how injury to the epithelium lining of the lung, a common consequence of viral infection, impacts the behavior of lung fibroblasts, the cells that are responsible for the aforementioned scar tissue formation. Nick showed that epithelial cells become “deranged” by viral injury and secrete several factors that directly promote more pathologic changes in the nearby fibroblasts, causing them to recruit more immune cells, driving chronic and inappropriate inflammation that in turn leads to increased tissue fibrosis. We are in the process of identifying all the relevant signals here in hopes of reversing the process to prevent this damaging consequence of severe injury.

What is the one thing you wish more people understood about your field?

That cutting-edge science is an evolving and dynamic process. We continually develop new conceptual models to better understand, describe, and predict biological processes. But for every major advance, there are almost always parts of the new models that are, if not outright wrong, at least incomplete. Science is not a stone tablet of hard and fast facts but rather represents our best attempts to describe our observations of the world around and within us.

What is the toughest challenge you face in advancing your work?

Scientifically, one of our biggest challenges is determining how to “reprogram” the injury-affected epithelial cells that inappropriately occupy the gas-exchanging alveolar area after injury into more physiologically appropriate cell types, called alveolar type 2 and type 1 cells that are needed for normal lung function.

I believe it’s essential to address another unfortunate reality facing the biomedical sciences at present: the lack of funding necessary to truly drive the fields forward and facilitate the next scientific breakthrough. An obvious recent “proof of principle” success story is the funding of basic research and the subsequent rapid scientific development of mRNA vaccines for COVID-19, which unquestionably saved millions of lives. Nevertheless, a significant fraction of the public and lawmakers remain distrustful of scientists. To compound this, NIH budgets adjusted for inflation have not increased substantially in over 20 years; in fact, by many measures, practical funding levels have decreased during that period. No matter how you slice it, scientific progress requires funding. I hope we, as a society, will do a better job of recognizing that reality and providing scientific research with the funding needed for future breakthroughs to occur.

What is a passion or favorite ritual outside of work that helps to keep you grounded?

I love to make beer, play the guitar, read comic books, and I’ve recently re-engaged with video gaming (I really love Metroidvania-style games). I’ve also become a little bit obsessed with stand-up paddleboarding over the last few years, going so far as to get a wetsuit so I can keep getting out there through November!

Related News

Behind the Breakthroughs: David Holt

In this edition, we sit down with small animal Professor of Surgery, David Holt, BVSc, DACVS. Dr. Holt is redefining how cancer is seen and removed during surgery. A Diplomate…

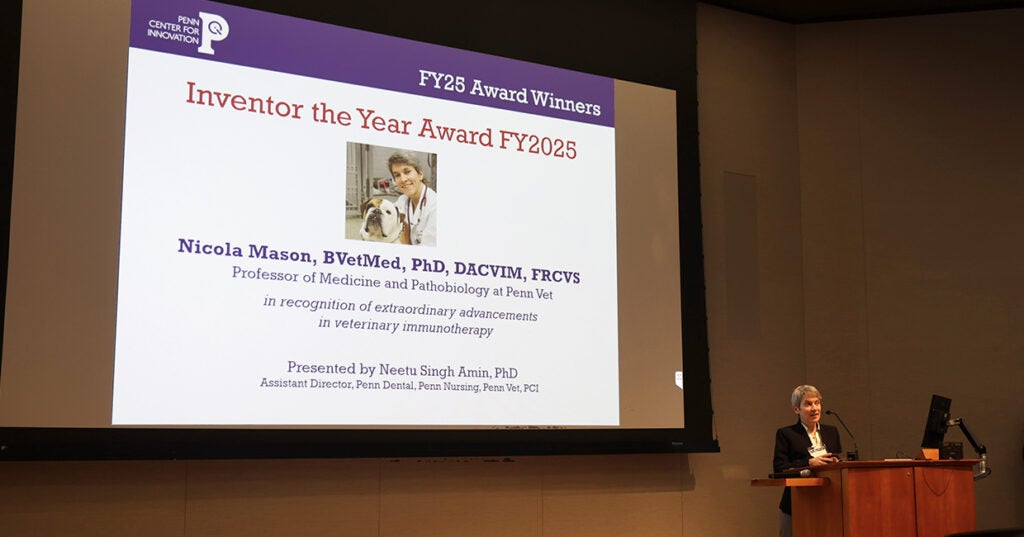

Penn Vet’s Nicola Mason, BVetMed, PhD, DACVIM, FRCVS, Receives Penn Center for Innovation’s Inventor of the Year Award

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn) School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) congratulates Dr. Nicky Mason, the Paul A. James and Charles A. Gilmore Endowed Chair Professor and Professor of Medicine…

Behind the Breakthroughs: Amy Johnson

Balancing clinical care with scientific inquiry, Penn Vet’s Amy Johnson leads efforts to decode the complexities of neurologic diseases in horses

About Penn Vet

Ranked among the top ten veterinary schools worldwide, the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) is a global leader in veterinary education, research, and clinical care. Founded in 1884, Penn Vet is the first veterinary school developed in association with a medical school. The school is a proud member of the One Health initiative, linking human, animal, and environmental health.

Penn Vet serves a diverse population of animals at its two campuses, which include extensive diagnostic and research laboratories. Ryan Hospital in Philadelphia provides care for dogs, cats, and other domestic/companion animals, handling more than 30,000 patient visits a year. New Bolton Center, Penn Vet’s large-animal hospital on nearly 700 acres in rural Kennett Square, PA, cares for horses and livestock/farm animals. The hospital handles more than 6,300 patient visits a year, while our Field Services have gone out on more than 5,500 farm service calls, treating some 22,400 patients at local farms. In addition, New Bolton Center’s campus includes a swine center, working dairy, and poultry unit that provide valuable research for the agriculture industry.