Ryan Hospital and New Bolton Center’s Infection Prevention and Biosecurity Programs Strive to Safeguard Health for Animals and People

Faculty In This Story

Drug-resistant bacteria are one of the most urgent health challenges of our time, affecting people, animals, and the environments they share. The University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) is addressing this evolving challenge with comprehensive infection prevention and control measures, as well as biosecurity strategies, to protect the animals, people, and communities served by its hospitals and facilities.

Ryan Hospital and New Bolton Center each have dedicated infection prevention and control (IPC) leaders responsible for developing, monitoring, and implementing disease control protocols, as well as educating staff and students on veterinary infection prevention. They’ve even brought in high-tech big guns – robots that zap microscopic offenders, eradicating them with blasts of ultraviolet germicidal (UV-C) light.

“Both Ryan Hospital and New Bolton Center have established robust infection prevention and control programs, striving to set the gold standard in veterinary medicine,” said Donna Oakley, CVT, Ryan Hospital’s director of clinical governance.

Ryan’s Hospital’s program got its start in response to an outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) at the hospital in 2018, which was among the first to ever be investigated in companion animals. Two of the leaders in forming a program to address antibiotic-resistant bacteria were Stephen D. Cole, VMD, DACVM, an assistant professor of clinical microbiology, who has extensively studied the emergence of CRE in pets, and Oakley.

CRE are listed as major antimicrobial resistance threats by both the World Health Organization and the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cole’s research has focused on tracking the spread of CRE in companion animals across the United States, including the first national prevalence study in dogs and cats

In a study published this year in Clinical Infectious Diseases, Cole and fellow researchers found strong evidence that CRE can be transmitted between animals and humans, making it a firmly established One Health issue.

Moreover, they are on the rise. A recent CDC report found a 460% increase in the type of CRE most often found in pets, according to Cole’s work, causing infections among people. “Much work still needs to be done to really determine what is driving this problem in people and pets,” Cole said, “but it is clear that veterinary hospitals need to respond to cases and CRE rapidly and efficiently in order to prevent their spread.”

The microbiologist has launched a resource program and lab, the CRE Animal Testing and Epidemiology (CREATE) Project, to help veterinarians respond to CRE. Cole, who collaborates with infectious disease researchers nationwide, believes Ryan Hospital has established one of the best IPC programs in the field.

“We implement evidence-based practices in an ever-changing environment to respond to concerns in real-time,” Cole said. “I think what is best about our program, though, is that we are committed to constantly making it even better to protect our patients, our community, and, ultimately, the world by stemming the tide of antimicrobial resistance.”

A significant step in building an IPC program was hiring Regina Wagner, JD, MSN, MHQS, RN, DNP Scholar, as Ryan Hospital’s first full-time infection prevention officer in 2022. Wagner, who has conducted similar work in human facilities such as the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, has developed over 20 policies specific to veterinary medicine and is implementing them.

“Our comprehensive IPC program integrates surveillance, policy development, research, quality improvement initiatives, and environmental strategies,” said Wagner. “As well as broader collaboration across our hospital units to prevent infections and safeguard patients, staff, and the community.”

“My bottom line is safety,” she said. “Of course, we have the best veterinarians in the world, and we have the most wonderful students and a wonderful hospital. We’re supporting them by providing ways that they can provide safe care through knowledgeable, data-driven infection prevention and control.”

Because animal hospitals aren’t regulated in the way that human hospitals are, full-time infection preventionists like Wagner aren’t the rule at veterinary facilities. Key elements of the rigorous program she has implemented include outreach and monitoring of hand hygiene. Posters, reminding staff about this basic but crucial step in infection prevention and control, are posted throughout Ryan.

In addition, Wagner collaborated with Penn Vet’s technology team to develop a hand hygiene app. She and others – including students, staff, and supervisors – function as trained observers, recording hand hygiene compliance on the app via their mobile phones. Since the system was instituted, Wagner said hand hygiene compliance has increased sevenfold. The transmission of measurable CREs has also dropped dramatically.

Educating new and future clinicians is an important part of what Wagner does.

“I do educational sessions with our interns, residents, and students,” she said. “Just recently, our V’27 class had to complete an online module and get an 80% or better on their exam in order to go into their clinical rotation. That’s giving them IPC knowledge before they start working with patients.”

Wagner also worked with Ryan Hospital’s environmental services team to develop new policies and procedures.

“We’re now doing over 1,000 cycles a year of UV-C disinfection (via robot), and those are not just in response to animals with an infection,” she said, compared to 300 cycles several years ago. “We’re also doing it prophylactically around the hospital on a scheduled basis.”

New Bolton Center’s arsenal – from household mainstays to high-tech wonders

Preventing Salmonella infections is one of New Bolton Center’s biggest challenges, although it is not the only resistant bacteria its IPC program does battle with.

Nevertheless, it was a 2004 Salmonella outbreak that led to a lengthy and challenging hospital closure as the entire facility was cleaned and disinfected repeatedly. Prior to that, the hospital had two partial closures. All in all, the facility wasn’t back to full operating capacity until January 2005. Following that long and difficult chapter, a dedicated director of biosecurity position was created for Helen Aceto, PhD, VMD, professor emerita.

Aliza Simeone, VMD, DACVPM, assistant professor of clinical infectious diseases and biosecurity and now New Bolton Center’s director of biosecurity, and Felicia Divito, biosecurity administrative coordinator, are at the forefront of implementing comprehensive protocols for cleaning and disinfection as well as maintaining an active environmental surveillance program, grouping patients according to their infectious risk category, and actively surveying the highest risk groups.

They also continuously utilize the data to refine their cleaning and disinfection protocols. Their tools range from mundane to futuristic.

“I use a Swiffer, and I go around, and I test various areas of the hospital on a routine schedule based on that area’s risk category,” Divito said. “Salmonella is ionically charged. It likes to attach itself to things, and that’s the way a Swiffer works. It holds onto the Salmonella quite nicely.”

“The reason it {Salmonella} is considered a problem in large animal hospitals is not necessarily because we do not have any other germs. It’s that Salmonella can be very persistent in the environment,” said Simeone.

Then there’s Tru-D. That’s the brand name of the UV-C-emitting robot the New Bolton Center crew has newly added to its arsenal of infection prevention. The robot, affectionately referred to as Trudy, offers pleasant banter unlike Ryan’s strong but silent triplet robots, and is very effective in eliminating Salmonella and other challenging organisms. “Trudy has reduced the need for repeat cleanings, often requiring heavy-duty cleaning chemicals,” Simeone said, emphasizing the benefits to cleaning personnel and the environment.

“{Using Tru-D} is better for morale for the whole team,” Divito said. “Our team is so passionate here. Prior to having Trudy, if they were cleaning something and it came up Salmonella-positive, they’d take it to heart that they hadn’t done a good job. Now we have a powerful backup.”

Simeone and Divito also provide education to students, clinicians, and personnel on infectious disease prevention, including everything from disease-specific precautions to general hand hygiene training.

They’ve gotten creative, too.

To help drive home a point playfully, they created an educational campaign centered on human food and beverage containers in patient care areas. “There was an issue with people having their personal food and drinks in patient care areas, which is a potential problem for personnel health,” Simeone said.

Historically, they had always removed these items from clinical spaces. Then, in early 2024, they took it a step further by performing aerobic cultures on the beverage containers found in patient care areas to see what germs were on them. Then they posted the often-nasty results, along with a photo of the removed mug on their bulletin board.

The name of this initiative was Biosecurity’s Most Wanted Mug Shots.

It didn’t have Tru-D’s bright lights, but it got people’s attention. It also led to a big decline in rogue coffee cups.

“It was a huge help,” Divito said.

Related News

$1.5 Million Gift from Nestlé Purina PetCare Company Fuels Growth of Canine Cognition and Performance Research at the Penn Vet Working Dog Center

The University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine’s (Penn Vet) Working Dog Center (WDC) has received a transformative $1.5 million gift from Nestlé Purina PetCare Company to establish the Purina…

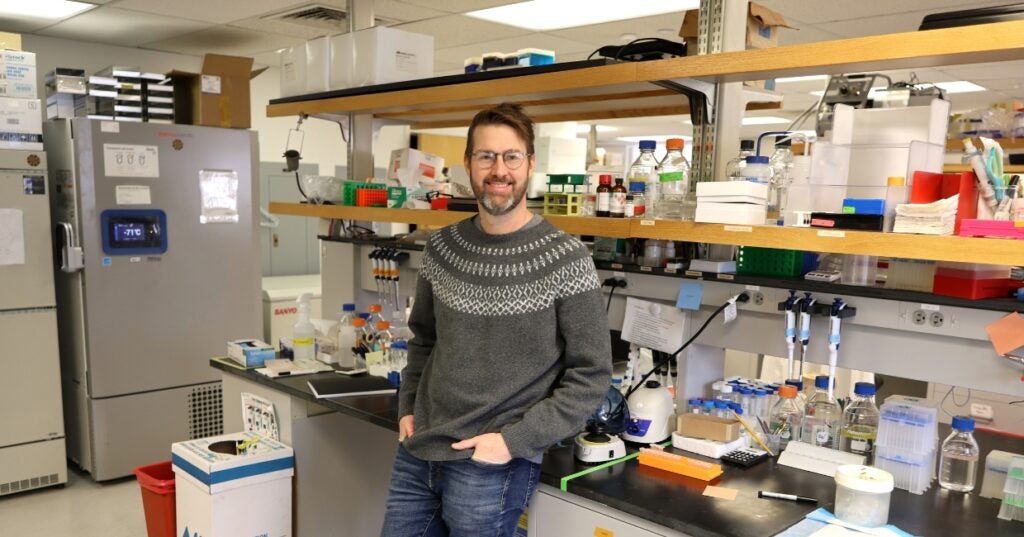

Behind the Breakthroughs: Andrew Vaughan

In this edition, we sit down with Associate Professor of Biomedical Sciences, Andrew “Andy” Vaughan, PhD. Vaughan is a molecular and cellular biologist with a specific interest in lung regeneration.

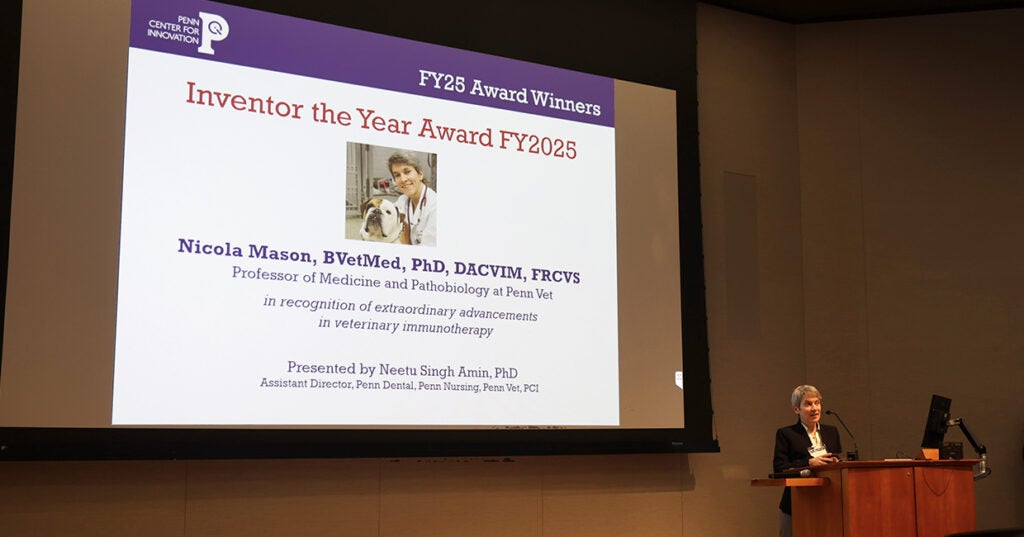

Penn Vet’s Nicola Mason, BVetMed, PhD, DACVIM, FRCVS, Receives Penn Center for Innovation’s Inventor of the Year Award

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn) School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) congratulates Dr. Nicky Mason, the Paul A. James and Charles A. Gilmore Endowed Chair Professor and Professor of Medicine…

About Penn Vet

Ranked among the top ten veterinary schools worldwide, the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) is a global leader in veterinary education, research, and clinical care. Founded in 1884, Penn Vet is the first veterinary school developed in association with a medical school. The school is a proud member of the One Health initiative, linking human, animal, and environmental health.

Penn Vet serves a diverse population of animals at its two campuses, which include extensive diagnostic and research laboratories. Ryan Hospital in Philadelphia provides care for dogs, cats, and other domestic/companion animals, handling more than 30,000 patient visits a year. New Bolton Center, Penn Vet’s large-animal hospital on nearly 700 acres in rural Kennett Square, PA, cares for horses and livestock/farm animals. The hospital handles more than 6,300 patient visits a year, while our Field Services have gone out on more than 5,500 farm service calls, treating some 22,400 patients at local farms. In addition, New Bolton Center’s campus includes a swine center, working dairy, and poultry unit that provide valuable research for the agriculture industry.