Research Brief

Translating Emerging Cancer Science into Effective Therapies

Beyond being devoted companions, dogs share essential aspects of their biology with humans. While cancer scientists frequently use cell lines and rodent models to study how diseases arise and respond to experimental therapies, dogs naturally develop many of the same cancer types as people do and respond to many of the same drugs and therapeutic approaches.

Two projects at Penn Vet are harnessing these similarities to generate new treatments and an enhanced scientific understanding of both canine and human cancers.

“The lines between human and veterinary medicine are starting to blur,” said Dr. Nicola Mason, the Paul A. James and Charles A. Gilmore Endowed Chair Professor in Penn Vet’s Department of Clinical Sciences and Advanced Medicine.

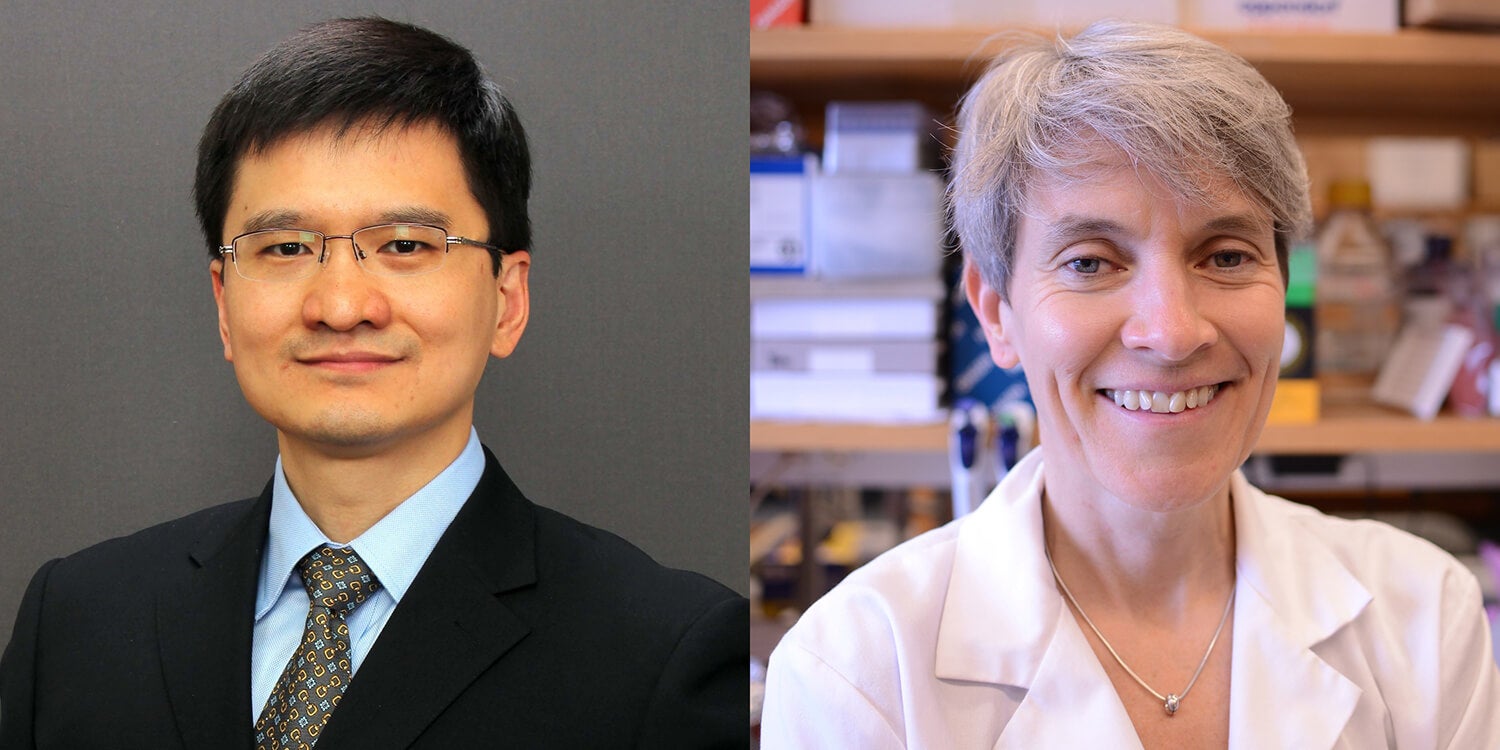

Back in 2017, as part of funding that arose from the Cancer Moonshot launched by then-Vice President Biden, a Penn Vet team led by Mason won a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) enabling the school to serve as the Data Coordinating Center for PRECINCT, short for Pre-medical Cancer Immunotherapy Network for Canine Trials. The Perelman School of Medicine’s Dr. Qi Long joined Mason as a co-lead in 2018 to enhance the project’s data science expertise.

In fall 2022, the Penn team was awarded another grant, providing more than $500,000 a year to continue that work for another five years, with a goal of furthering scientific research to identify new immunotherapies that may translate from dogs to humans.

The coordinating center collects clinical trial data from 10 veterinary and medical academic sites — five awarded in 2017 and an additional five awarded in 2022 — across the country. In doing so, the center ensures each trial acquires high-quality data in a standardized way from canine patients receiving cutting-edge combination immunotherapies.

“Within this network we have a collaborative and interactive group of veterinary and medical clinician scientists who are advancing clinical translation of novel immunotherapeutics in canine patients and discovering correlative biomarkers of response that will inform future human studies,” said Mason.

The center and network represent a growing recognition of the value of comparative oncology, especially when dogs, as a “parallel patient population,” as they are called, bear such similarities to humans.

“The Data Coordinating Center is laying the groundwork to ensure that clinicians — doctors and veterinarians alike — have the best evidence at hand when it comes to selecting treatment plans for their cancer patients,” said Dr. Ellen Puré, director of the Penn Vet Cancer Center and the Grace Lansing Lambert Professor of Biomedical Science in the School of Veterinary Medicine.

In a second initiative, another Penn Vet-Penn Medicine pairing is pushing a cutting-edge therapeutic strategy closer to potential clinical application.

Dr. Brian Flesner, an oncologist at Penn Vet, and Dr. Keith Cengel, a radiation oncologist at the Perelman School of Medicine, are jointly studying a novel approach to radiation therapy that may one day benefit people and pets.

Their investigation, supported by the Mark Foundation and IBA, focuses on the use of palliative radiation therapy, which can slow tumor growth and reduce pain, but typically requires treatments over several weeks or months. In contrast, the technique Cengel and Flesner are piloting, known as FLASH radiation, is — as the name indicates — far speedier. Patients can receive a palliative course of radiation in just a few visits.

FLASH radiation is also believed to cause less toxicity than traditional approaches, due to the transient and highly precise nature of the radiation exposure. Following an initial study of the technique in dogs with osteosarcoma begun in 2019, this new trial is using a precisely directed proton beam to target smaller tumors of the oral cavity. The energy of the positively charged particles in the proton beam destroys cancer cells, while penetrating deeply into tissue. This therapy may also spare normal tissues that surround the tumor from being damaged, a “potentially game-changing” outcome, Flesner said.

If the results prove promising in canine cancer patients, it may open the door to exploring the use of the technique in people, the researchers say. “We think FLASH is going to be safer and hopefully as efficacious as a standard radiation therapy,” said Flesner.

In the future, the team hopes to extend their study to include cats, to target different tumor types, and to use electrons instead of protons, which don’t penetrate as deeply. Eventually the goal is to refine protocols for performing the technique in people with various types of cancer.

Last fall, Dr. Meg Ruller, V’18, enrolled her dog Maple, a then- 13-year-old yellow Labrador retriever, to be the first dog treated in the trial. Maple received two courses of FLASH radiation for a maxillary osteosarcoma, and Ruller saw some subsequent improvement in the tumor site. Maple passed away in early January. But Ruller said the trial not only gave her beloved companion a chance at a better quality of life in her final months, but also felt “like the right move,” given that Maple spent her life as a service dog.

“Being part of a clinical trial, for her, it’s kind of a full-circle moment,” Ruller said. “I like the idea that she is still in service.”

More from Bellwether

In the Office with Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM

Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM, shares her New Bolton Center office with the campus’s microbiology reference library.

Breaking New Ground: Penn Vet Builds Future-Ready Learning Hub

Set to open in the coming months, the 11,800-square-foot clinical skills center will be the first dedicated classroom space on the Kennett Square campus, ushering in a new era of…

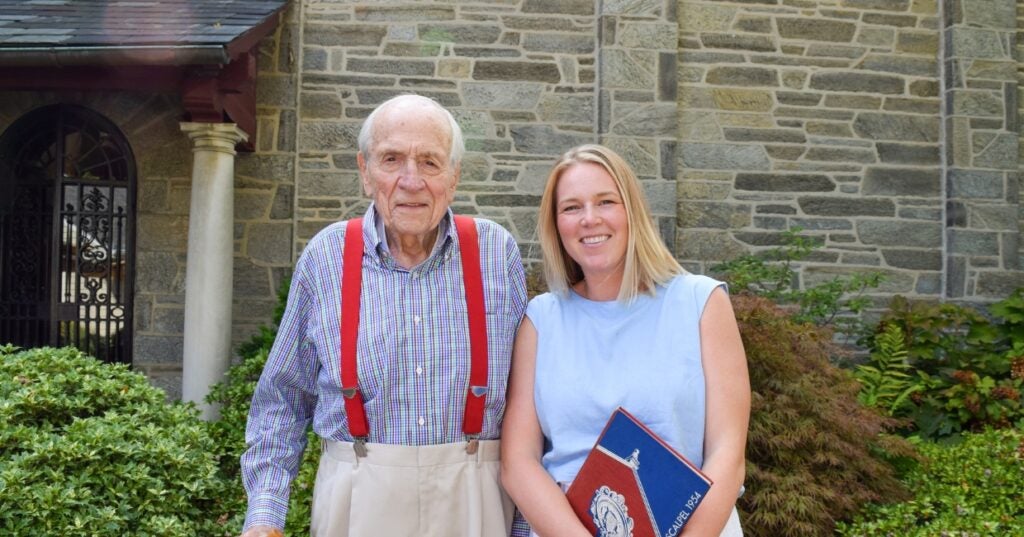

A Love of Animals and the Land

The Penn Vet of Dean Snyder, V’54, was a very different place than today. So was the world.