Penn Vet News

Featured News

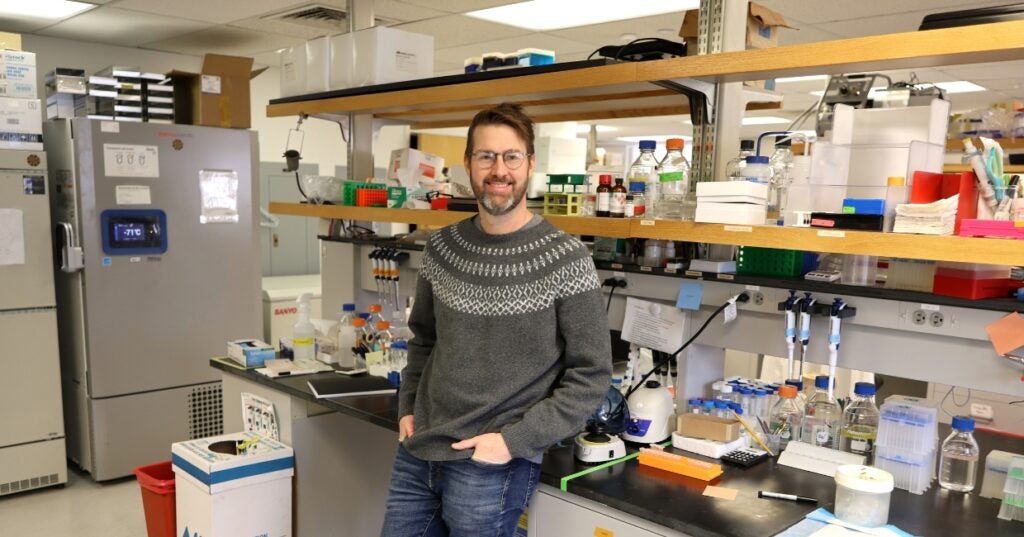

Behind the Breakthroughs: Andrew Vaughan

In this edition, we sit down with Associate Professor of Biomedical Sciences, Andrew “Andy” Vaughan, PhD. Vaughan is a molecular and cellular biologist with a specific interest in lung regeneration.

$1.5 Million Gift from Nestlé Purina PetCare Company Fuels Growth of Canine Cognition and Performance Research at the Penn Vet Working Dog Center

The University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine’s (Penn Vet) Working Dog Center (WDC) has received a transformative $1.5 million gift from Nestlé Purina PetCare Company to establish the Purina…

Penn Today News

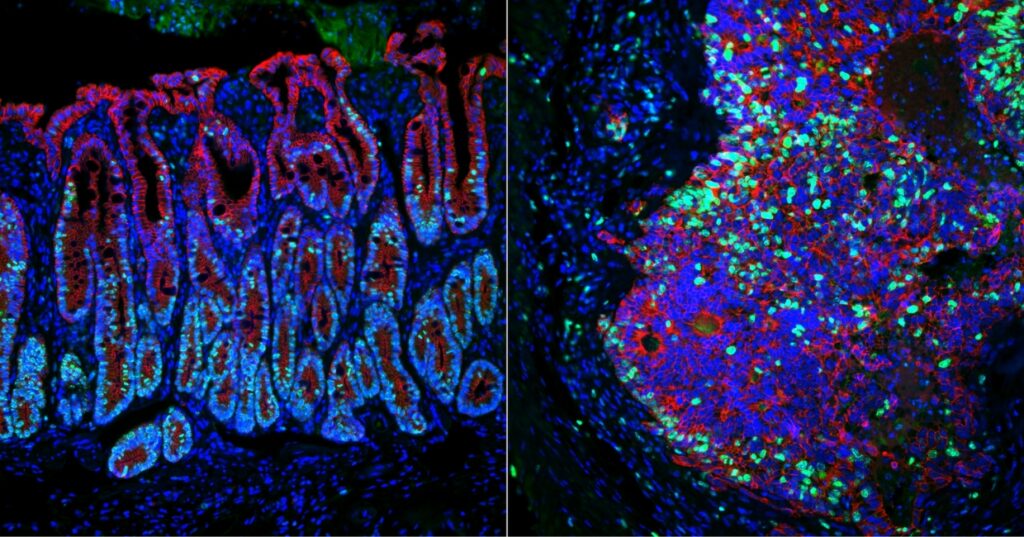

Identifying genes that keep cancer from spreading (link is external)

Using a novel approach, Penn Vet’s Chris Lengner and M. Andrés Blanco and colleagues have identified two genes that suppress colorectal cancer metastasis.

Wild birds are driving the current U.S. bird flu outbreak (link is external)

Since late 2021, a panzootic, or “a pandemic in animals,” of highly pathogenic bird flu variant H5N1 has devastated wild birds, agriculture, and mammals.

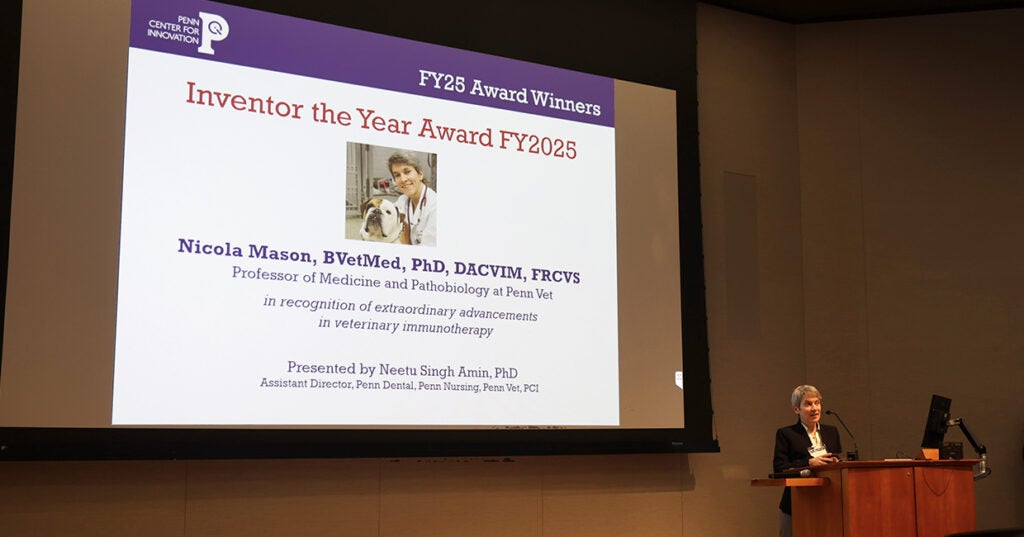

Dogs with cancer are helping save lives—both canine and human (link is external)

The Comparative Immunotherapy Program led by Penn Vet’s Nicola Mason is redefining how therapies are developed and tested—uniting human and veterinary medicine to move promising immunotherapies forward.

In the Media

Bellwether Features

Unboxing a Pioneer’s Legacy

Born in 1919, Jane Hinton, V’49, came of age when opportunities for women in science and medicine were scarce — and for Black women, nearly nonexistent. expertise in poultry and…

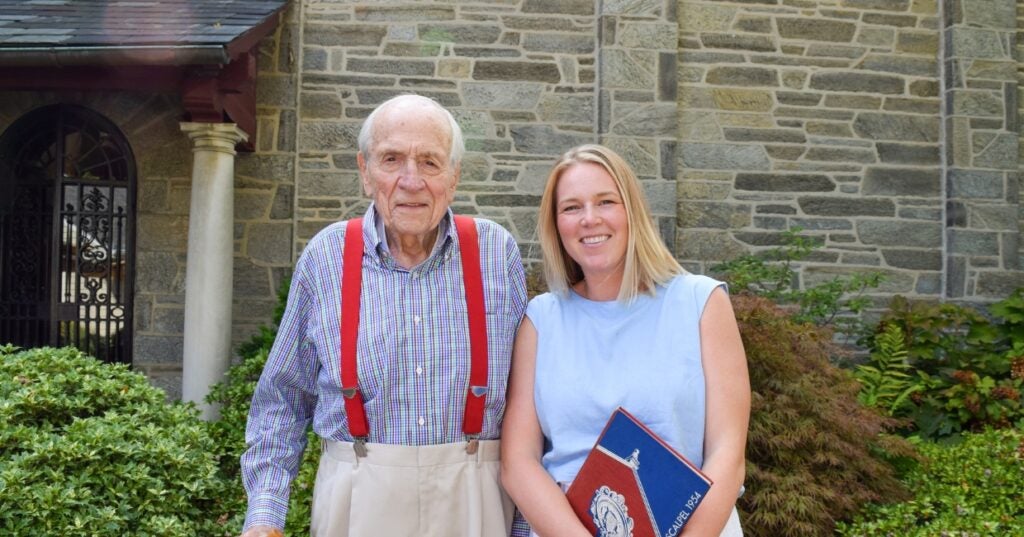

A Love of Animals and the Land

The Penn Vet of Dean Snyder, V’54, was a very different place than today. So was the world.

Comforting Philanthropy

At Penn Vet’s Ryan Hospital, world-class clinical care is matched with deep compassion for animals and the people who love them.

In the Office with Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM

Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM, shares her New Bolton Center office with the campus’s microbiology reference library.

For the media

Press Inquiry

For all press inquiries, please the form below. This form is for media purposes only. If you are an animal owner, contact Ryan Veterinary Hospital for Companion Animals or, for our large animal hospital, New Bolton Center.

Non-News, Commerce-Affiliated Content Site Inquiries

The Office of Communications is selective in responding to requests from freelance writers on assignment for non-news, content building sites.

- All interviews with clinicians, faculty, staff and/or students in association with Penn Vet, Ryan Hospital, or New Bolton Center must be arranged through and facilitated by a representative from the Office of Communications. Please do not contact such individuals directly.

- When submitting a media or interview inquiry, please fill out this form. Include your name, contact information, and general details of your pitch including important deadlines.

- Visits to Penn Vet’s campuses and/or hospitals by members of the media must be arranged directly through a representative from the Office of Communications. For the well-being and privacy of our animal patients and their owners, a representative from the Office of Communications must also accompany any arranged visits.

- If an interview requires a Penn Vet clinician, faculty or staff member, or a student to be recorded on video, please be aware that a signed copy of the University’s video authorization form must be submitted to and confirmed by a representative from the Office of Communications prior to any taping. Additionally, an an Appearance Release must be supplied to the Office of Communications for review and approval prior to obtaining a signed agreement from the individual that is to appear on camera.