Behind the Breakthroughs: Amy Johnson

Pushing the Boundaries of Equine Neurology in the Field and the Lab

Balancing clinical care with scientific inquiry, Penn Vet’s Amy Johnson leads efforts to decode the complexities of neurologic diseases in horses.

Behind the Breakthroughs is a Q&A series that shines a light on the people and ideas driving discoveries across Penn Vet. Each installment offers a glimpse into the work and the curiosity that fuel breakthroughs in basic, translational, and clinical science.

In this edition, we sit down with Marilyn M. Simpson Professor of Equine Medicine, Amy Johnson, DVM, DACVIM (Large Animal Internal Medicine and Neurology). Johnson was the first American veterinarian and the second veterinarian in the world to receive dual certification in neurology and large animal internal medicine from the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine. Her work targets one of the field’s most elusive challenges: diagnosing neurologic diseases in living horses. Partnering with pathologists across institutions, she is mapping brain lesions, investigating behavioral changes, and preparing to introduce brain proton emission tomography (PET) imaging to equine medicine. The results promise to transform how veterinarians understand and treat neurologic dysfunction, advancing equine welfare and offering parallels to human neurodegenerative research.

What big problem is your research aiming to solve?

My research career has focused on improving our ability to diagnose neurologic diseases in horses. The development of diagnostic tests, imaging equipment, and surgical techniques for neurologic problems has lagged in horses compared to other species because of their large size. Historically, diagnosis relied heavily on postmortem examination, with limited ability to confirm diagnoses in living horses and subsequent difficulty in enacting successful treatment protocols.

“During my time at Penn, we’ve made huge strides in the diagnosis of infectious neurologic diseases and structural vertebral column problems.”

However, we still have a lot to learn about neurodegenerative disease, commonly termed equine degenerative myeloencephalopathy (EDM) or equine neuroaxonal dystrophy (eNAD). Neurodegenerative disease is one of the primary causes of neurologic dysfunction in horses, with many commonalities to human neurodegenerative disease such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease). It typically causes progressive loss of coordination and strength as well as changes in demeanor and behavior that can cause the horse to manifest unpredictable and undesirable behaviors. Right now, the only way to confirm the presence of neurodegenerative disease is to examine multiple parts of the horse’s brain and spinal cord under a microscope, which is not conducive to diagnosis in the living horse. I would like to identify biomarkers in spinal fluid or blood as well as an imaging technique that would permit diagnosis in my clinical patients. That would provide earlier detection, evaluation of treatment strategies, and better decision-making surrounding the future of potentially affected horses.

What is the flagship project that you are working on right now?

It is hard to pick just one! There are several related ongoing projects to increase our understanding of neurodegenerative disease and its causes. One challenge we’ve faced is that the behavioral manifestations of the disease are profound and often the most concerning aspect, but we previously didn’t understand why they were occurring or the extent of risk involved when working with affected horses. The ‘classic’ pathologic lesions associated with EDM are not in areas of the brain that modulate behavior, nor did early descriptions of EDM document the hazardous behaviors that are common in our patients.

We have formed an EDM research group with a team of pathologists at Penn Vet, University of Kentucky’s Gluck Equine Research Center, and Cornell Vet to examine the brains of well-characterized cases, and we are discovering lesions in higher brain centers that have not been described previously but are likely related to behavioral abnormalities. Additionally, we are actively recruiting affected and control horses into a study that includes an extensive owner survey as well as analysis of systemic endocrine and gastrointestinal health to learn more about potential predisposing risk factors and observed behaviors.

Finally, the project I’m most excited about hasn’t started yet! We are on our way to developing the capability to perform brain proton emission tomography (PET) scans in horses, which will give us a window into brain function that we’ve never had before, and potentially provide us with means to diagnose and monitor neurodegenerative disease in living horses.

What is the one thing you wish more people understood about your field?

My field is very, very small, and the disease is very difficult to study, which can be a frustrating combination for accomplishing research goals! I think some people assume there are many researchers focused on EDM, when I can count the number of people on one hand. Small fields lack resources, which means we must be extraordinarily collaborative and resourceful to get anything done. Additionally, people don’t understand how challenging and stressful the process of diagnosing neurologic disease can be in horses. Signs of neurodegenerative disease are insidious and subtle, mimicking dozens of other potential problems and complicating clinical research.

“However, failure to diagnose disease can have grave consequences considering the hazards a neurologic horse presents to itself, other animals, its handlers, and its riders.”

Most of my patients weigh more than 1,200 pounds, and an unexpected stumble, fall, or kick can seriously injure or kill the horse or those around it. This creates an urgency to accomplish our research goals, with pressure to find diagnostic and treatment methods despite scarce funding and man (woman) power.

What is the toughest challenge you face in advancing your work?

Personally, my toughest challenge is time. My faculty position includes a large clinical commitment, and as the only equine neurologist on the east coast, I have a lot of patients to see! I’ve always considered myself a clinician at heart, with a strong desire to help horses and the people surrounding them. It’s hard to step away from the clinic and dedicate large amounts of time to research. For the last 2.5 years, thanks to the generosity of my clients, I have been blessed with an equine neurology fellow, Dr. Sarah Colmer, who has increased the amount of research work we can accomplish. Retaining Sarah and building our group of collaborators are priorities to allow our work to continue to advance.

What is a passion or favorite ritual – outside of your research and work – that helps to keep you grounded/balanced?

Before I wanted to be a veterinarian, I was pretty sure I would be a gym teacher – sports were a constant part of my life. My primary sport was field hockey, which I played competitively for 13 years, including four years on Franklin Field as part of Penn’s collegiate team! Now that I have three sports-loving children (Annie,13; Michael, 10; Cora, 8) I spend a lot of time outside on the sidelines or in a gym, cheering them on and coaching Annie’s and Cora’s field hockey teams. Coaching at an elementary and middle school level helps keep me young and on my toes. It also makes me appreciate the attention span and dedication of the professional students and veterinarians I teach at Penn!

Related News

Behind the Breakthroughs: Andrew Vaughan

In this edition, we sit down with Associate Professor of Biomedical Sciences, Andrew “Andy” Vaughan, PhD. Vaughan is a molecular and cellular biologist with a specific interest in lung regeneration.

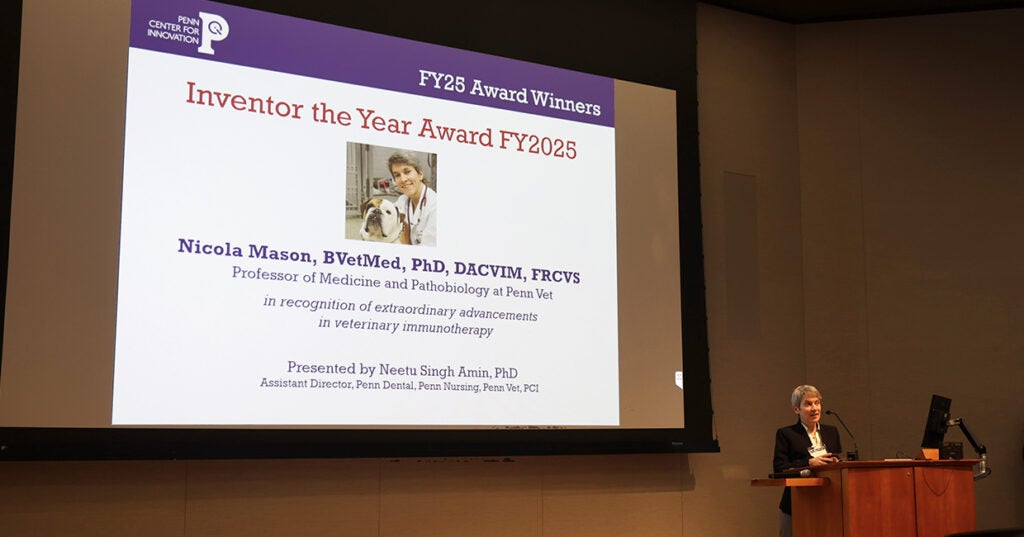

Penn Vet’s Nicola Mason, BVetMed, PhD, DACVIM, FRCVS, Receives Penn Center for Innovation’s Inventor of the Year Award

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn) School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) congratulates Dr. Nicky Mason, the Paul A. James and Charles A. Gilmore Endowed Chair Professor and Professor of Medicine…

In the Office with Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM

Donna Kelly, DVM, MASCP, DACPV, DACVPM, shares her New Bolton Center office with the campus’s microbiology reference library.

About Penn Vet

Ranked among the top ten veterinary schools worldwide, the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) is a global leader in veterinary education, research, and clinical care. Founded in 1884, Penn Vet is the first veterinary school developed in association with a medical school. The school is a proud member of the One Health initiative, linking human, animal, and environmental health.

Penn Vet serves a diverse population of animals at its two campuses, which include extensive diagnostic and research laboratories. Ryan Hospital in Philadelphia provides care for dogs, cats, and other domestic/companion animals, handling more than 30,000 patient visits a year. New Bolton Center, Penn Vet’s large-animal hospital on nearly 700 acres in rural Kennett Square, PA, cares for horses and livestock/farm animals. The hospital handles more than 6,300 patient visits a year, while our Field Services have gone out on more than 5,500 farm service calls, treating some 22,400 patients at local farms. In addition, New Bolton Center’s campus includes a swine center, working dairy, and poultry unit that provide valuable research for the agriculture industry.