New Bolton Center Surgeons Come Through for Howee the Steer and his Girl

Mallie Touchton was always a farm animal kid. Since she was 8, Mallie was raising and showing her own market livestock – pigs, goats, and dairy calves. Even though she always knew she’d have to say goodbye, she got attached to them all.

But Howee was special. He was her first steer, a jet-black Simmental cross. He was only six months old when she got him, but he was going to be big. To prepare a large animal like Howee for showing, Mallie raised him with plenty of halter training, regular walkabouts, lots of grooming – including shampoos and blow dries.

Suffice to say, the Lancaster County teen and her steer developed a bond. By the time he was a year old, Howee ran to greet Mallie every time she came to his gate.

And sure enough, Howee was at his gate one morning last April to greet his girl, but Mallie could tell something was wrong.

“He was standing kind of funny, and his eyes were wide,” Mallie said. And the clincher: Howee showed no interest in the food she put out for him.

Mallie wasted no time. She found her father, Josh Touchton.

“ ‘You need to call the vet. Something is not right,’ ’’ Josh recalled his daughter telling him. Despite her youth, he didn’t doubt her judgement. “She was that in tune with him,” he said.

The local veterinarian didn’t waste time, either. Seeing the steer was dripping urine, she suspected a blockage. Get him to Penn Vet’s New Bolton Center, she advised. Josh has his own animal hauling business, Touchton Livestock. So, he and Mallie loaded up Howee and drove him to New Bolton Center hospital themselves that night.

At the hospital, the emergency service confirmed Howee had a urinary obstruction by doing an ultrasound of his bladder, said Marie-Eve Fecteau, section chief of large animal surgery. Urine was removed from Howee’s bladder with a needle-like implement, and he was stabilized with intravenous fluids and pain medications, with surgery planned for the following morning.

Howee’s obstruction was commonly referred to as stones, actually sand-like particles that can become compacted and form blockages in an animal’s urethra, making urination difficult or in Howee’s case, impossible. In addition to the discomfort the animal suffers, the build-up of toxins can lead to other serious health problems within just a couple of days, according to Fecteau, who is a professor of farm animal medicine and surgery.

Surgical relief for a special steer

The next day, two New Bolton veterinarians performed a tube cystostomy on Howee to drain his bladder. With the steer under general anesthesia, they opened his bladder and removed the stones, said Fecteau, who was not one of the initial participating surgeons for that procedure. They then installed a special catheter that was intended to reroute his urine flow for the next two weeks. The hope was that the stones remaining in Howee’s urethra would pass on their own.

But that did not happen. As Howee continued to be monitored, Fecteau, who had at that point taken on the case, and the Touchtons discussed alternatives.

Mallie, of course, was very concerned about Howee.

“I was really worried because I wasn’t really sure what was happening,” she said. Still, Mallie, who has wanted to be a large animal veterinarian ever since she and her family can remember, had faith. “I trusted those veterinarians because I know they know what they’re doing.”

Urinary tract stones are not uncommon for ruminants, but New Bolton Center’s veterinarians are usually asked to perform surgery on animals like pet goats, Fecteau said, not steers which eventually head to market.

Euthanasia was an option raised and dismissed.

Fecteau suggested another possibility: it was a surgery called perineal urethrostomy, or PU. With that procedure, urine flow is permanently rerouted, so the animal is no longer urinating from the tip of its urethra, the surgeon explained. Instead, a new opening is made just below the animal’s anus. It is not a long-term solution, she said. Depending on the animal’s lifespan, it may need to be done again. For some animals, it can be very short term. Like the initial surgery, many owners don’t opt to have it performed on their cattle. They just send the animal to market sooner.

Josh Touchton, with a lifetime in livestock, understood how some would make that choice. But when the time came for the surgery, he was all in.

“With a farm background and raising animals for market, I’m thinking, ‘This is crazy.’ But at the same time, I was thinking it’s my daughter’s show animal that she had already shown a couple of times. So we needed to do as much as we could.”

According to Fecteau, giving animals the best possible life in the time they have is what drives farm and food animal veterinarians, a branch of the profession suffering a serious shortage.

“The main reason we go into this field is that even though we know many of the patients we treat end up being utilized for food production, we hope that while we oversee their care, we’re able to institute the husbandry and care that we know is going to impact their lives in a healthy way,” she said.

“We treat populations of animals, but we also treat individual animals, and we go above and beyond, like applying state of the art medicine to them as well,” Fecteau said.

Howee’s care ended up requiring almost a full month at the New Bolton Center.

The Touchtons came for visits. Mallie treated Howee with hay from home. For Easter, she brought him bunny ears, just as for Halloween back home, she had dressed him up as a ghost.

Active in the Future Farmers of America, Mallie’s goal was to show Howee in the big annual Solanco Fair in September. She’d already shown Howee at some other competitions, but her hopes were always set on Solanco. Mallie appreciated how the New Bolton Center team let her spend time with Howee, even allowing her to take him walking like she would at home. “One intern, I heard, was in there brushing him every day,” she said.

Meanwhile, Fecteau and Josh Touchton were in frequent contact about Howee and his progress. Fecteau even sent the Touchtons photographs.

“Our experience was great,” said Josh. “They kept us in the loop the whole time. And I feel like they went above and beyond because it was for a kid.”

Before the Touchtons decided to go ahead with the PU surgery, they checked with the Solanco Fair governance committee to see if the procedure would disqualify Howee from the competition because his anatomy would be altered.

“They were all like, ‘If it keeps the animal healthy and gets it to the show, then let’s work with that.’ Nobody was against it,” Josh said.

Still, he wasn’t sure if Howee was actually going to be OK. Then not long after the surgery, he heard from Fecteau. It was near the end of April.

“She told me she watched him pee. She was ecstatic. She told me, ‘He can go home very soon,’” Josh recalled. “Within a few days, we were bringing him home.”

The road to the big fair

Back in Lancaster County, Howee kept getting stronger, and he and Mallie continued to train.

The Solanco Fair was held September 17 to 19. On September 18, Howee was named Division Champion Middle Weight Steer. The Touchtons made sure to let Fecteau know. Mallie just was so proud.

“When Howee and I got champion at the fair, I was overly happy not just because we had gotten champion, but because Howee had made it to the show ring,” she said.

The next day, September 19, Howee was auctioned, as Mallie always knew he would be.

“I was really sad to see him go. I always am, but this one was definitely extra special because of all that happened,” Mallie said.

She knows some people might not understand, but she said raising animals helps young people like her learn the skills they need in the agriculture field, and in life. Skills like time management and responsibility. The money she earns from showing enables her to support the animals in her care. In early November, Mallie brought home her new steer, a red crossbreed she named Clifford. He and Howee have the same father.

“I do still miss Howee sometimes,” she said. “It’s a little bittersweet not having him in the barn.”

Someday soon, Mallie hopes to take Fecteau up on her invitation for a tour of the New Bolton Center. The Solanco High School sophomore has heard there is a shortage of farm veterinarians. That, and everything that happened with Howee has inspired her.

“This experience pushed me more to want to work to become a vet because the vets really helped me,” Mallie said. “They really helped me understand everything they were doing to Howee. I want to be able to help younger kids and families.”

Related News

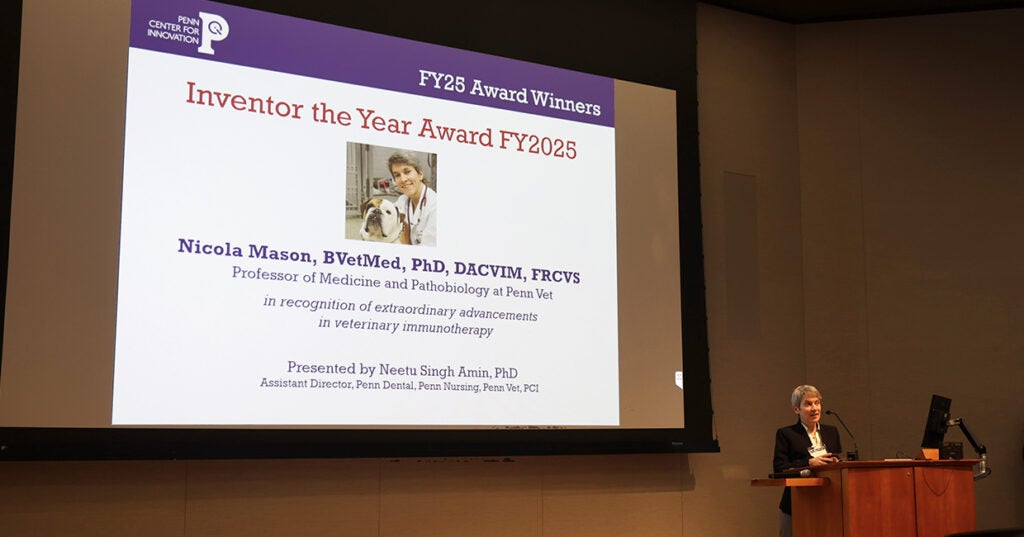

Penn Vet’s Nicola Mason, BVetMed, PhD, DACVIM, FRCVS, Receives Penn Center for Innovation’s Inventor of the Year Award

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn) School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) congratulates Dr. Nicky Mason, the Paul A. James and Charles A. Gilmore Endowed Chair Professor and Professor of Medicine…

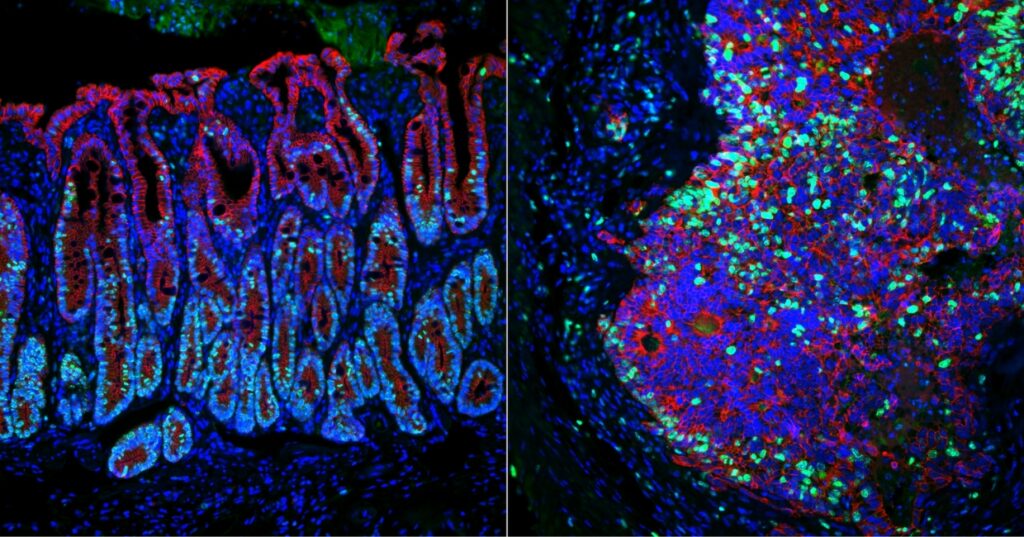

Identifying genes that keep cancer from spreading (link is external)

Using a novel approach, Penn Vet’s Chris Lengner and M. Andrés Blanco and colleagues have identified two genes that suppress colorectal cancer metastasis.

About Penn Vet

Ranked among the top ten veterinary schools worldwide, the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet) is a global leader in veterinary education, research, and clinical care. Founded in 1884, Penn Vet is the first veterinary school developed in association with a medical school. The school is a proud member of the One Health initiative, linking human, animal, and environmental health.

Penn Vet serves a diverse population of animals at its two campuses, which include extensive diagnostic and research laboratories. Ryan Hospital in Philadelphia provides care for dogs, cats, and other domestic/companion animals, handling more than 30,000 patient visits a year. New Bolton Center, Penn Vet’s large-animal hospital on nearly 700 acres in rural Kennett Square, PA, cares for horses and livestock/farm animals. The hospital handles more than 6,300 patient visits a year, while our Field Services have gone out on more than 5,500 farm service calls, treating some 22,400 patients at local farms. In addition, New Bolton Center’s campus includes a swine center, working dairy, and poultry unit that provide valuable research for the agriculture industry.