A few dozen enthusiastic students arrived at the School of Veterinary Medicine’s New Bolton Center campus in Kennett Square this fall, ready to transform a portion of the rural landscape. Their efforts set the stage for a more-sustainable farming model.

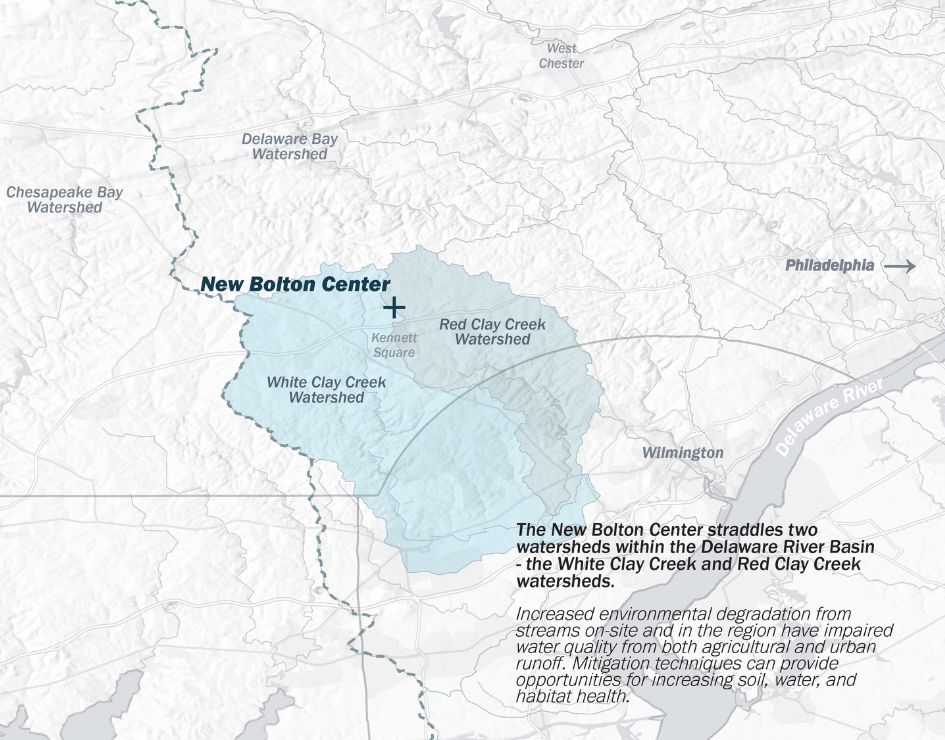

The Penn Regenerative Ag Alliance, one of the Environmental Innovations Initiative’s research communities, is embarking on this journey as part of a larger project recently funded by the William Penn Foundation. Crossing disciplinary silos, Alliance leader Thomas Parsons, director of Penn Vet’s Center for Stewardship Agriculture and Food Security, and Ellen Neises, executive director of Penn Praxis at the Weitzman School of Design, joined forces with a team from the Stroud Water Research Center. They used principles of agroforestry to design a land-use plan that aims to both protect the local watershed and breathe new life into fallow land by combining the planting of trees and shrubs with grazing of marginal farm ground. A major goal was to help improve the water quality and health of the White Clay Creek, as its headwaters reside on the New Bolton Center campus, but also develop new “win-win” models of animal agriculture that provide both economic benefits and ecological services.

Map of the New Bolton Center and regional watersheds within the Delaware River Basin

Map of regional watersheds within the Delaware River Basin (Image: Courtesy of Elliot Bullen)

Map of the New Bolton Center and regional watersheds within the Delaware River Basin

Map of regional watersheds within the Delaware River Basin (Image: Courtesy of Elliot Bullen)

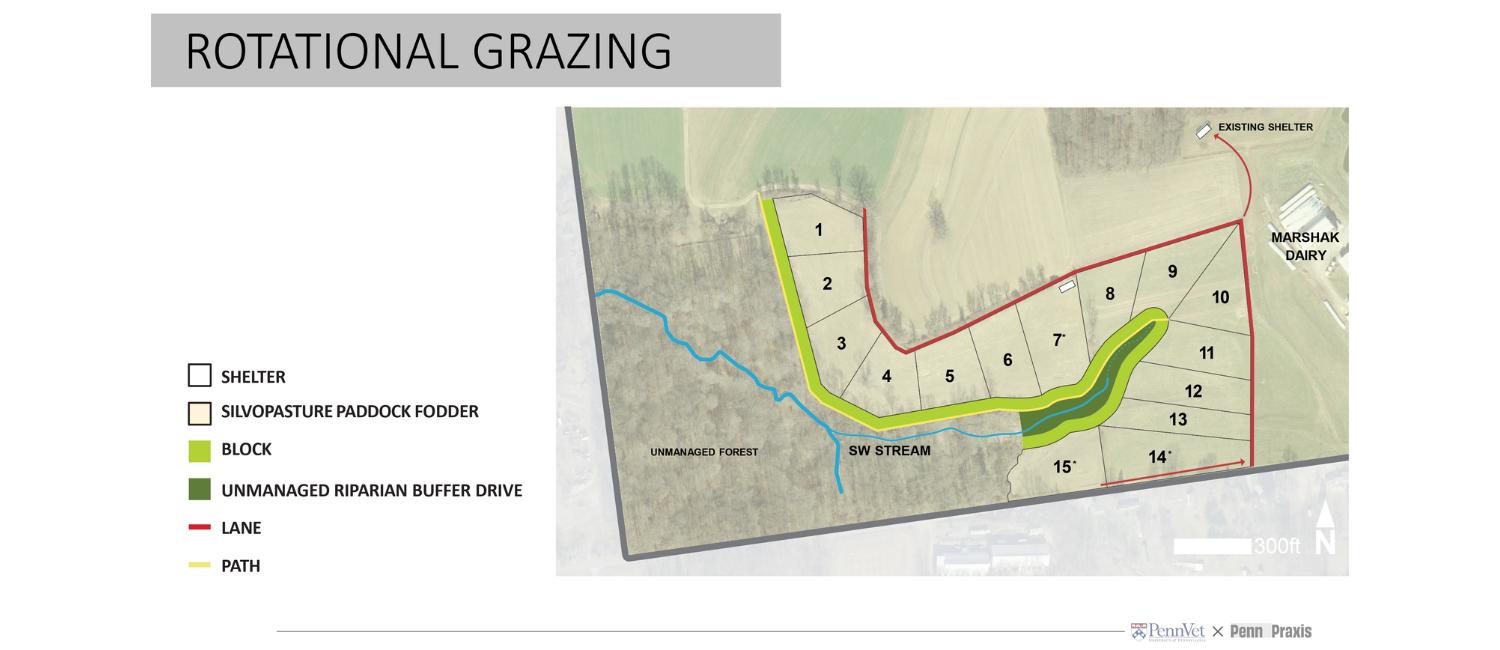

Over the summer, Elliot Bullen, project manager, and two Penn Praxis fellows began a spatial analysis to assess suitable species for the landscape design of a 20-acre rotational grazing system for ruminants. The initial plant list focused on native tree and shrub species that might provide benefits such as food or shelter for animals. Penn Vet experts helped narrow the choices by eliminating species that might pose a risk to animals living within this agroforestry system. For instance, a honey locust tree will provide cows dappled shade in the warmer months and in the fall as pasture grasses become dormant, and drop pods that provide a supplemental food source to the animals. However, the team needed to find honey locust varieties that are thornless, as the more common thorned varieties could pose a challenge for operating farm equipment and to the cows themselves.

Agroforestry in Action

After the agroforestry design was complete, it was time for community engagement and implementation. A few dozen students and faculty volunteered to help during a full fall day, planting 250 trees in total. “One of the biggest logistical challenges was to get people from the city to NBC for the tree planting, about a one-hour drive from Philadelphia,” said Bullen. “We recruited lots of enthusiastic volunteers and students carpooled to the site.”

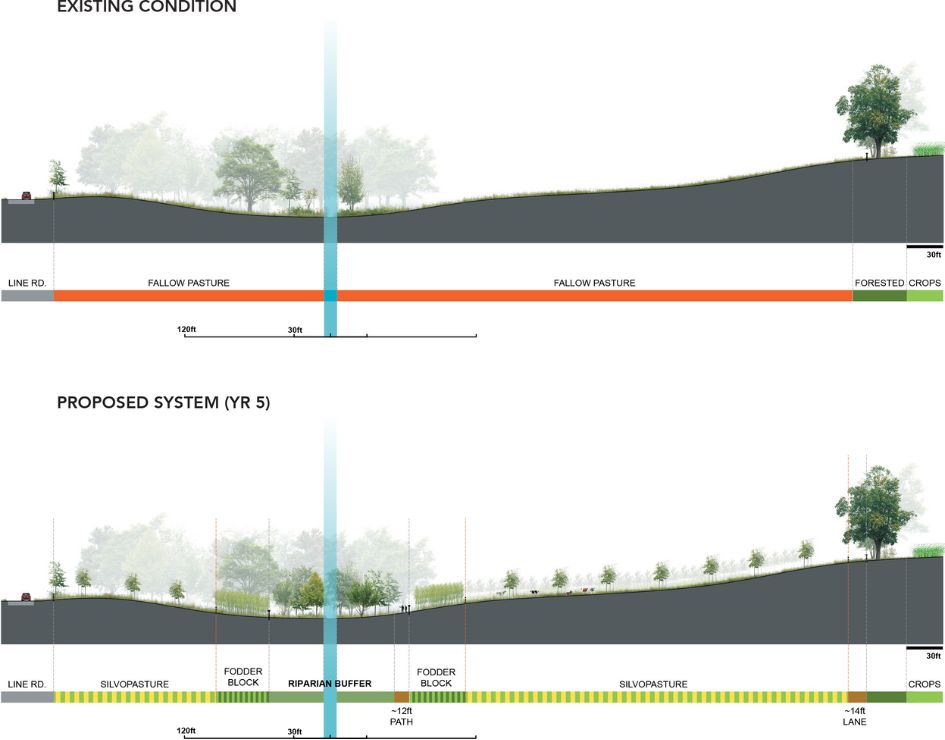

In the area nearest the stream, known as the riparian zone, volunteers planted 16 species that thrive in wet conditions. Among them, one-year-old sycamores, spicebush, and magnolias will mature enough in four to five years to meaningfully stabilize the streambanks and provide shade to cool the water. Stroud Water Research Center staff Matt Ehrhart, Lamonte Garber, and Heather Titanich sourced plants and guided the implementation of the riparian buffer. In addition to providing shade to regulate water temperature and shelter crucial ecological processes, the network of roots in the riparian buffer reduce soil erosion and keep excess nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous from reaching the stream.

“…waiting is the main difference between landscape and architecture. When you finish your project in architecture, that is the best it will look. In landscape, it takes time” – Elliot Bullen

Jointly with the Stroud team, the Alliance will monitor water quality and stream health within the agroforestry system, using this data to inform new models of animal agriculture that farmers in the region can reproduce to enhance and protect their local watersheds.

A section view comparing the existing condition and proposed system

A section view of the existing site and proposed agroforestry (Image: Courtesy of Elliot Bullen)

A section view comparing the existing condition and proposed system

A section view of the existing site and proposed agroforestry (Image: Courtesy of Elliot Bullen)

Maintaining Momentum: More Construction and Long-term Monitoring Systems

Two areas of the design remain to be built, including a section of native shrubs palatable to cows and a silvopasture area. As its name indicates, silvopasture integrates trees into pastureland, benefiting animals and grass biodiversity. “It looks more like a savannah than a forest because the distribution of the trees is spread out, providing shade to the animals in summer and increasing the pasture grasses’ resilience,” Bullen says. In addition to shade, the trees also produce forage and edible fruits for the animals. A longer-term goal is to use the shrubs and trees as living fences to help define transient grazing areas for the animals as they traverse the agroforestry system.

Looking toward the future, agroforestry project team will be working on long-term monitoring systems, are planning a BioBlitz to catalog biodiversity at the site, and will leverage their New Bolton Center experience to advance similar agroforestry systems on farms in the region. This initiative extends the efforts of Penn Vet’s Center for Stewardship Agriculture and Food Security to make animal agriculture part of the solution to a more resilient, sustainable, and equitable future. The agroforestry team is eager to engage more students, researchers, and faculty in the project, with opportunities to visit NBC, participate in future planting events, and even create new studies associated with the land. There is lots of room, literally and figuratively, for people and ideas within this living laboratory at NBC.

Agroforestry site layout including silvopasture and riparian buffer

Agroforestry layout of rotational grazing (Image: Courtesy of Thomas D. Parsons)

Agroforestry site layout including silvopasture and riparian buffer

Agroforestry layout of rotational grazing (Image: Courtesy of Thomas D. Parsons)