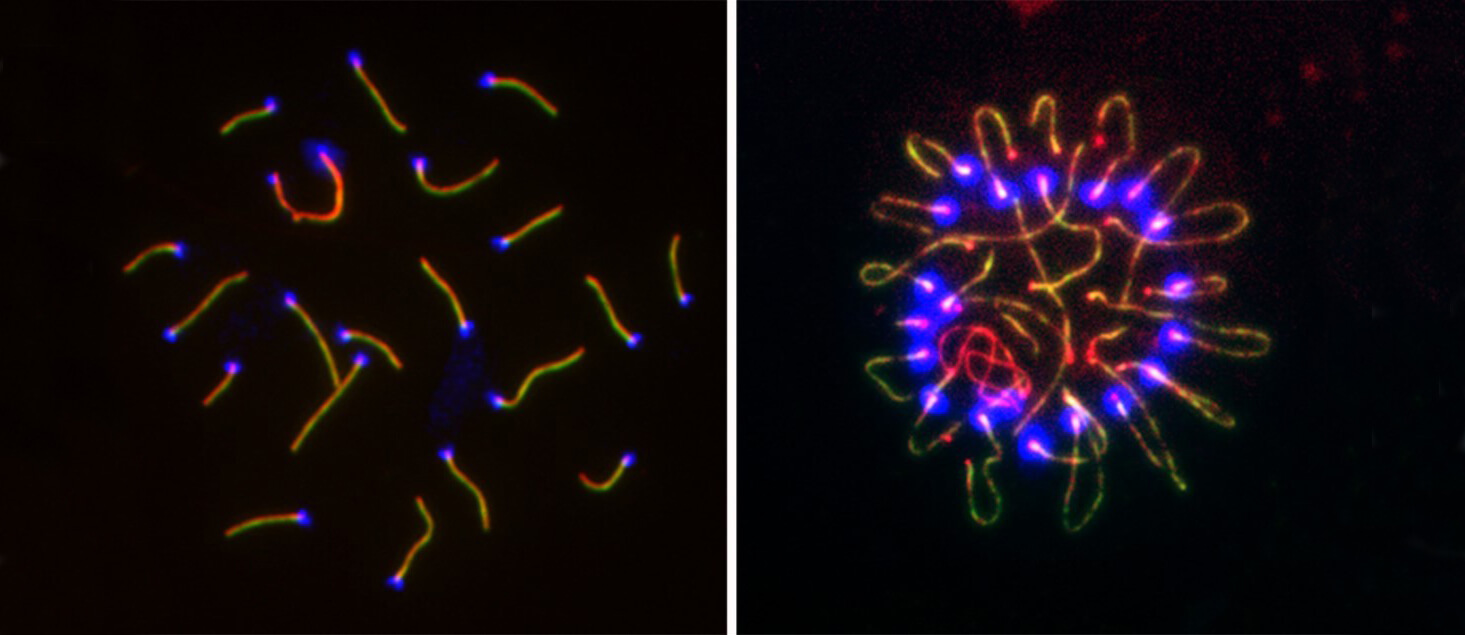

P. Jeremy Wang and colleagues explore meiosis, the special type of cells division that gives rise to germ cells, sperm and eggs. In one recent study, inactivating the gene YTHDC2,

P. Jeremy Wang and colleagues explore meiosis, the special type of cells division that gives rise to germ cells, sperm and eggs. In one recent study, inactivating the gene YTHDC2,

which is required for meiosis to progress through all of its proper stages, led to an odd clustering of chromosome ends (at right).

Reproduction is a complex process, requiring a huge variety of molecular and cellular interactions, many aspects of which remain a mystery to science.

Dr. P. Jeremy Wang

Dr. P. Jeremy Wang

Solving some of these mysteries drives the curiosity and research of P. Jeremy Wang, professor of developmental biology in the School of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Biomedical Sciences. Wang also directs the Center for Animal Transgenesis and Germ Cell Research. For the last two decades, his lab has focused on understanding the process of meiosis, the special type of cell division that gives rise to germ cells: sperm and eggs.

Three recently published studies illuminate some of the diverse strands of the Wang lab’s research.

Sperm motility and a potential contraceptive target

By whipping their tails, known as flagella, sperm propel themselves through the female reproductive tract. Interacting with and moving through the zona pellucida, the thick coating that shrouds eggs, is energetically demanding. That stage of fertilization is powered by the activity of a calcium ion channel formed by a protein complex known as CatSper.

In the journal Development, Wang and colleagues describe a newly identified component of CatSper, a protein called C2CD6. Wang’s team found that inactivating C2CD6 did not affect females but rendered males sterile. “Their sperm count is normal, their sperm look normal, but they weren’t able to produce pups,” Wang says.

The protein’s location in the flagellum suggested a possible role in sperm motility.

And, indeed, the team found that C2CD6-deficient sperm were unable to enter what's known as “hyperactivation,” where a ramping up in calcium channel signaling gives sperm the burst of energy required to penetrate the zona pellucida. The work underscores the essential nature of this component of the CatSper complex; C2CD6 is in fact so essential, Wang says, that it could facilitate a drug screening system to find a male contraceptive.

“A lot of people have thought about targeting the CatSper complex for a contraceptive,” Wang says. “Knowing this component of the complex might help scientists test which compounds would effectively stop sperm from being able to fertilize an egg.”

Recurrent pregnancy loss

A second recent study, described in Biology of Reproduction, looks at the female side of the reproductive process, specifically, what happens when it goes awry. In studying the CCNB3 gene, located on the X chromosome and believed to function in meiosis, Wang and colleagues found that male mice lacking CCNB3 appeared normal. But females, while they could become pregnant, lost the pregnancy at an early stage.

Detailed analysis by Wang and his team uncovered why these miscarriages arise. They found that CCNB3—mutations which occur in humans as well—normally helps meiosis progress. When the gene is not functioning normally, eggs that should have only one set of chromosomes wind up with two sets. That means a fertilized egg, with a set contributed from a sperm, would wind up with three sets of chromosomes, a genetic scenario incompatible with life.

The finding “has translational value,” Wang says.

“With personalized or precision medicine, if a woman gets their genome sequenced and knows they have this mutation, doctors could take their egg, add a functional version of CCNB3 to rescue the defect, and then perform in vitro fertilization and end up with a normal embryo.”

A new role in meiosis

A third publication returns to the bread and butter of Wang’s research: the intricacies of meiosis. In the journal Cell Reports, Wang and his team uncovered a new way in which YTHDC2, an RNA-binding protein, operates during the cell division process.

Other research groups had previously studied this protein, conducting genetic knockout experiments, where the gene was fully inactivated, to show that it acted during the early stages of meiosis.

Wang’s lab, however, employed a different technique whereby they could allow YTHDC2 to function until meiosis had already begun. By doing so, they found that the protein had a second role later in meiosis, acting to maintain what’s known as the pachytene stage, the lengthiest meiosis stage, lasting six full days.

“It looks like YTHDC2 is a master regulator,” says Wang. “It appears to bind to RNA and help degrade or silence transcripts that are not supposed to be there, helping the cell commit to meiosis and allow the process to progress.” While no YTHDC2 mutations have been found in humans linked with infertility, Wang says, “it’s just a matter of time.”

Future work in the Wang lab will pick up where some of these findings left off, continuing to uncover the workings of these fundamental processes.

These studies were supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants HD069592, HD068157, HD038082, HD088571, GM108556, HD03185, HD069592, and GM118052), China Scholarship Council fellowship, Swiss National Science Foundation, National Key Research & Development Program of China, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and Human Frontier Science Program.