Researchers from the School of Veterinary Medicine have shown that an enzyme that suppresses early-stage colorectal cancer switches to become an oncogene as the cancer progresses.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, and only around 10% of patients survive for five years after being diagnosed. In a new study, published in the journal Gut, a University of Pennsylvania-led team of researchers have identified a potential treatment target for advanced CRC. When they inhibited the enzyme NOTUM in an animal model of CRC, it effectively halted tumor growth and prevented the cancer from becoming metastatic. However, the same treatment was not effective in treating earlier stages of cancer because NOTUM only becomes an oncogene—a factor that the cancer needs to grow and spread—as cancer progresses.

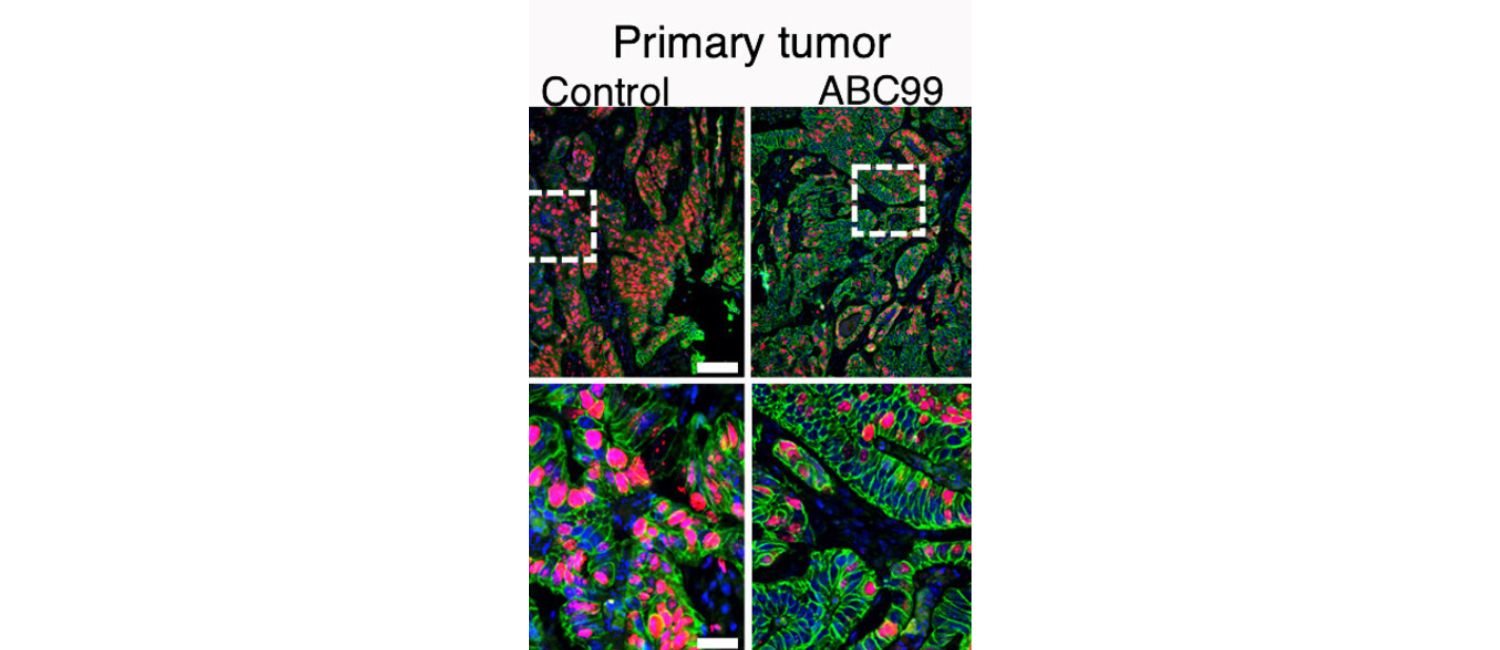

Inhibiting the enzyme NOTUM slowed cancer growth and prevented metastasis in an animal model of colorectal cancer. (Image: Yuhua Tian)

“Tumor behavior eludes simple classification because tumor cells effectively employ genes to ensure their survival and growth, sometimes with disregard to conventional characterization as oncogenes or suppressors,” says co-senior author Ning Li, in the School of Veterinary Medicine.

More than 80% of CRC cases involve a mutation in a tumor suppressor factor called APC. In healthy cells, APC controls the rate of cell division for epithelial cells in the gut by suppressing the WNT pathway, a pathway that regulates how stem cells divide in terms of both the rate at which they divide, and what type of cell they become. When APC is mutated, it takes the brake off of WNT, resulting in uncontrolled cell division—one of the hallmarks of cancer.

However, APC isn’t the only inhibitor of the WNT pathway; there are also extracellular feedback mechanisms that help to keep it in check. One of these is NOTUM, an enzyme that cells secrete into the extracellular space. Li and co-senior author Penn Vet’s Chris Lengner wanted to investigate NOTUM’s role in colorectal cancer progression because its extracellular location and enzymatic activity make it an attractive drug target compared to intracellular or non-enzymatic molecules.

To do this, the researchers grew human and mouse organoids—clumps of cells—in the lab. They used CRISPR technology to introduce mutations associated with different stages of CRC, because cancer cells accumulate well-established mutations as cancer progresses. Then, they tested the impact of switching NOTUM on and off for normal cells, early-, mid-, and late-stage cancer cells.

The researchers found that in normal cells and in early-stage adenomas that are only missing functional APC, NOTUM suppressed cell division and thus inhibited tumor growth. However, as cancer progressed such that both APC and another tumor suppressor, P53, were inactivated, the researchers were surprised to find that NOTUM switched from being a suppressor to an oncogene. This is highly relevant given that APC and P53 are the two most commonly mutated genes in colon cancer, and many patients with late-stage disease harbor both mutations.

“There’s a genetic switch where if cells lose both APC and P53 together, that somehow converts NOTUM from a tumor suppressor to an oncogene,” says Lengner. “The function just completely does a 180°.”

The findings held up when the team re-tested NOTUM using different methods, and they also found that the pattern is mirrored in human patient data in the Cancer Genome Atlas. When the researchers suppressed NOTUM in a mouse model of CRC, it effectively slowed tumor growth, prevented metastasis, and extended the animals’ survival.

Using genetic techniques, the researchers determined that this switch in NOTUM’s behavior is caused by changes in its interactions with protein-carbohydrate complexes called glypicans on the cell surface, but more research is needed to delineate this mechanism.

However, NOTUM inhibition might not be a clinically viable treatment strategy in human patients, because although suppressing NOTUM may help to control aggressive, late-stage tumors, it might aid the progression of other cancer cells within the same patient that only carry the APC mutation. The researchers think that glypicans might be a more effective target for selectively inhibiting this pathway, and this is where they plan to focus their efforts next.

The researchers say that these findings might also offer insight into why many clinical cancer trials have failed. Preclinical cancer models usually only focus on defined versions or genotypes of the disease, so a treatment that is very successful in this narrow context might fail when tested against a more diverse patient population (with a diverse array of mutations) in a phase 1 or 2 clinical trial.

“The notion of personalized medicine looms large here,” says Lengner. “If you just focus on patients that have the version of the disease or the suite of mutations that you know work in the preclinical space, it might be a more efficacious way to run your trials.”

This study also suggests that caution may be needed for another potential application of NOTUM inhibition: NOTUM inhibition has been explored (in mice) as a way to rejuvenate aging epithelial cells, but if doing so increases the risk of cancer, it would not be a good idea.

“If you give a NOTUM inhibitor to an aged intestine that has perfectly normal APC, then yes, it will help restore stem cell activity, but if there are cells in that intestine that have lost APC, it might accelerate tumorigenesis,” says Lengner. “And once you hit a certain age, APC loss is essentially inevitable—think of colon polyps found in colonoscopies, these are usually APC-null lesions—so there’s a word of caution there.”

Christopher Lengner is the Harriet Ellison Woodward Professor and chair of the Department of Biomedical Sciences in the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

Ning Li is a research assistant professor at Penn Vet.

Other authors of the paper are Xin Wang, Zvi Cramer, Joshua Rhoades, Katrina N. Estep, Stephanie Adams-Tzivelekidis, Bryson W. Katona, F Brad Johnson, M. Andres Blanco, and Yuhua Tian of the University of Pennsylvania, Xianghui Ma of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Zhengquan Yu of Zhengzhou University.

Funding for this research came from the National Cancer Institute (Grants R01CA168654 and R50CA22184), and a grant from the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.